Author: Freddy Rothman

It was August 1944. The war was rapidly moving beyond the borders of the USSR. People were returning from evacuation, and life was settling into a peaceful rhythm. The Soviet repressive apparatus, too, was returning to its “peacetime” work. In a classified report on the Jewish poet David Hofstein, Deputy Chief of the 2nd Directorate of the NKGB of the Ukrainian SSR, Yakov Gersonsky, concluded: Hofstein is a nationalist who, upon returning to Ukraine, reactivated Zionist activity.

David Hofstein had come under the watchful eye of the Soviet security services long before the Great Patriotic War. He was hard to overlook – his entire biography spoke for itself. He was born on June 24, 1889, in the Jewish shtetl of Korostyshev in the Kyiv region, into the family of a carpenter, Nechemia Hofstein, and a homemaker, Alta-Khasi Kholodenko. In addition to David, the family had six other children. One of the poet’s sisters, Shifra Kholodenko, also became a Yiddish poet and translator.

The Hofstein family was modest and deeply religious. David’s maternal grandfather, Arn-Moyshe Kholodenko, also known as Pedtser, was a famous 19th-century klezmer musician. According to Hasidic tradition, his violin could “reveal the secrets of the Torah to listeners.”

After studying at a heder (traditional Jewish religious school), David spent some time teaching in the village of Bartkova Rudnya in the Zhytomyr region, where his family had relocated. In 1912, he was drafted into active military service, which he served in the Caucasus. There, eager for knowledge, the young man took external exams and earned his high school diploma. After the army, Hofstein studied at the Kyiv Commercial Institute, while also attending philology lectures at St. Vladimir University, and later at the St. Petersburg Psycho-Neurological Institute.

David Hofstein had been writing poetry since childhood – initially in Hebrew, later also in Russian and Ukrainian, and from 1909 onward in his native language, Yiddish. In the pivotal year of 1917, Hofstein began publishing his work. His debut as a poet took place in the Kyiv newspaper Naye Tsayt (“New Times”), the press organ of the Jewish Socialist Workers Party Fareynikte, with which the young writer was then collaborating as a journalist. Immediately after his first poetry collection, he published another book of poems, along with a collection of plays for children.

The young poet’s recognition by readers coincided with his emergence as a public figure. The Revolution promised liberation for the Jewish people, who had long been openly discriminated against in the Russian Empire. David Hofstein himself had encountered this systemic injustice multiple times – after the army, he was forced to apply to a commercial institute due to the Jewish quota in most imperial universities. He eagerly joined the struggle for equality.

In 1918, Hofstein worked in the Jewish Department of the Ukrainian Central Rada. In Kyiv, along with his work for Naye Tsayt, he also helped edit the anthology Eygns, and was involved with the publishing house Wider-Vuks, where he oversaw the publication of books by emerging poets. In 1919, his first poetry collection Bay Vegn (By the Roads) was published in Kyiv.

The Communists, who had solidified their control in Ukraine, promised the development of Jewish culture and the complete elimination of national inequality. In 1920, David Naumovich moved to Moscow, where he joined the Jewish literary circle Shtrom and became one of the editors of its monthly literary magazine of the same name.

The journal’s appearance almost immediately drew sharp criticism from writers aligned with Bolshevik ideology. The conflict between the “proletarianized” Jewish cultural camp and Hofstein’s supporters continued until January 1924. That year, Hofstein, along with other cultural figures, sent a letter to Mikhail Kalinin, then the nominal head of state and Chairman of the Central Executive Committee. The letter openly criticized the persecution of Hebrew – from the closure of schools to the ban on importing Hebrew-language literature from abroad.

This letter became the pretext for removing Hofstein from the editorial board of Shtrom. However, the staff reshuffling did not save the magazine, which was shut down shortly afterward.

The Jewish poet was forced to leave Moscow for Berlin. In Germany, David Hofstein continued working with the Jewish press. And in April 1925, he made one of the most profound discoveries of his life: Eretz Israel. Together with his wife, Feiga Semyonovna Biberman, he arrived in Palestine for the opening of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem – and they stayed.

Soon, David Naumovich found a job at the Tel Aviv municipality (according to some sources, at the local branch of the Jewish National Fund – Keren Kayemet LeIsrael). In addition to his work as a civil servant, he actively published articles and poetry in Hebrew in the local press. It was there, in the historic homeland, that David and Feiga welcomed the birth of their daughter, Levia. According to his wife’s recollections, that year in Palestine was a truly happy one for Hofstein. He rode his bicycle to work, undeterred by the heat or the khamsin winds, soaking in the colors, scents, and sights of the beloved land.

However, the happy days in the land of his ancestors did not last long. From his first marriage, Hofstein had two sons – Shamai and Hillel – who lived in Kyiv. Their mother, Ginda-Gitl Khait, had died back in 1920, and the children were left in the care of Hofstein’s parents. Deeply missing his sons, David Naumovich decided to return to the USSR. He was also troubled by the fact that he primarily wrote in Yiddish, a language that was being actively marginalized in Palestine at the time.

In 1927, David Naumovich returned to Kyiv. Feiga Semyonovna was able to join him from Palestine with their daughter only a few years later – and only after receiving special permission from high-ranking Party officials.

By the late 1920s, freedom of artistic expression in the Soviet Union had become a thing of the past. If you wanted to work in literature, you had to join the Jewish section of the All-Ukrainian Union of Proletarian Writers. Hofstein became a member of this organization’s bureau, and in 1928 began working on the editorial board of its journal Prolit. However, just a year later, the poet refused to participate in the persecution of his friend, Yiddish poet Lev Kvitko, and was promptly expelled from the writers’ union.

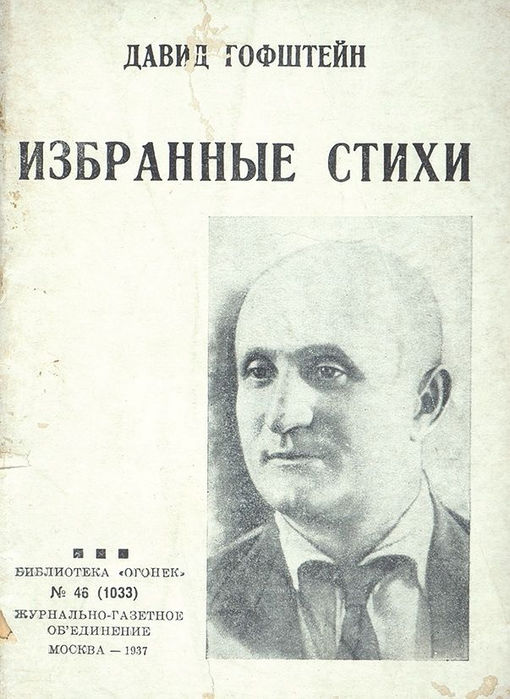

Eventually, Hofstein was forgiven and reinstated in the Jewish section of the Union of Soviet Writers. Between 1935 and 1937, he published several collections in Moscow, and in 1939 was even awarded the Order of the Badge of Honor. He actively translated from Ukrainian, Russian, and Georgian, and continued publishing his own works in the Soviet press. He also managed to teach at a Jewish trade union school and at the directing department of the Theater Institute in Kyiv.

During the years of the Great Patriotic War, David Naumovich was a member of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. In late June 1941, he managed to evacuate from Kyiv to Ufa, but his parents, brother Akiva, paternal grandfather Shamai, grandmother Gitl, and many friends and colleagues remained in the city. All of them were murdered by the Nazis in Babi Yar.

The poet was devastated by this horrific tragedy. While in evacuation, he wrote fervently: about the coming victory over the brown plague, about heroic partisans, and about the peoples of the USSR fighting to the last drop of blood.

Despite the poet’s patriotic stance, numerous informants and agents trailed Hofstein closely. According to an NKVD report, in 1942, during a business trip to Moscow, Hofstein made remarks in conversations with colleagues that were described as Zionist in nature. In Soviet terms, a Zionist was considered an enemy of the people – even if he was also an anti-fascist.

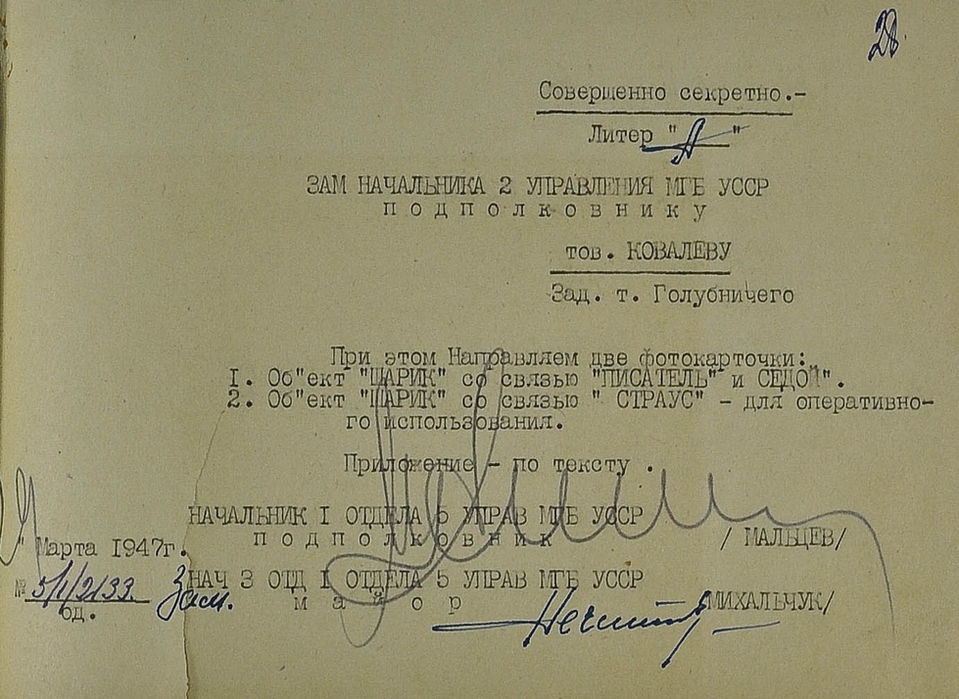

Following a report by Major Gersonsky from Moscow on October 2, 1944, an order was issued to intensify surveillance of the “nationalist” Hofstein, to document everything and collect compromising material for a planned arrest. They didn’t have to wait long. On March 26, 1945, the 2nd Directorate of the NKGB of the Ukrainian SSR opened an agent file named “Circle” targeting a group of Jewish writers living in Kyiv. The case was assigned to an experienced security officer, Shevko, head of the 3rd Department. Alongside David Hofstein, the file listed other writers and poets as subjects: Isaac Kipnis, Abram Kogan, and Riva Balyasnaya.

Hofstein and his colleagues were accused of Zionism, of actively corresponding with Jewish nationalists in cities across the Soviet Union, and of spreading slander about Soviet national policy.

Highly trained Jewish agents were sent to “win Hofstein over.” Among them was Serafimov, a well-known journalist and employee of the Department of Arts, code-named Administrator, and a writer from Chernivtsi, Kant. The latter had already reported to the NKVD in 1938 that Hofstein was the author of an “ultranationalist” piece, “The Song of My Indifference”, published in the journal Shtrom under the influence of the “rampant NEPmen.”

Kant claimed that while living in Palestine, Hofstein not only published in the local press but also distributed articles worldwide calling for the planting of forests in Eretz Israel. Kant also authored a literary analysis of Hofstein’s work for the security services. According to this “expert,” Hofstein’s early work was indeed of high artistic quality, but later – he wrote in clichés, produced hackwork, and demonstrated one thing: a lack of sincerity toward Soviet power. A seasoned criminal!

Another agent, code-named Semenov, a professor at Kyiv State University and translator who had been recruited in 1935 to monitor foreign tourists, reported in November 1945 that Hofstein lamented the plight of the Jewish people in the Soviet Union.

A colleague and friend of the writer, agent Serafimov, who often dropped by the very hospitable Hofstein’s home for tea, reported that David Naumovich not only spoke favorably of Zionism, but openly called himself a Zionist, advocating for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. “If not in the center of Moscow, then somewhere on Maroseyka there will be a place for a Palestinian representation. As for me, in my creative world, Palestine will have its place,” Serafimov quoted Hofstein as saying.

No operation was carried out to install listening devices in the writer’s apartment: intelligence had determined that Hofstein did not have a home telephone. However, all of his correspondence – both domestic and international – was intercepted and thoroughly examined by the “Department V” of the NKGB of the Ukrainian SSR.

In his letters, Hofstein expressed his views on Jewish culture quite openly. In a postcard sent in January 1946 to Itsik Kipnis, Hofstein wrote: “Hebrew to me is a father, for whom I long greatly; Yiddish is my mother, part of me and my adornment.”

The writer never abandoned his heartfelt attitude toward Hebrew, which was banned in the Soviet Union. On November 16, 1946, at an unofficial gathering of Jewish writers, David Naumovich spoke against the closure of the Jewish Culture Department at the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR. And not only did he oppose the decision – he made a counterproposal: that everyone present address the Central Committee of the Party with a request to open a separate Institute of Jewish Culture and to permit research and creative work in the field of Hebrew.

The other attendees did not support Hofstein’s proposal, but the Ministry of State Security immediately sent a report on Hofstein’s “incident” to the Ukrainian Party leadership.

Serafimov reported to “the appropriate authorities” that David Hofstein was spreading among the intelligentsia a “rumor”: that after the liberation of Ukraine, Jews were being barred from entering many major cities and were being excluded from key positions.

After the war, Hofstein wrote a play titled Mother, which reflected his deep concern for the condition of the Jewish population in the USSR. Only the blind could deny the existence of discrimination – but everyone else remained silent. The poet could not remain silent, and he envisioned a way out of the situation: “The play is grim, but what do you want from me? Do you want me to shout ‘hurrah’? … If it were up to me, I would give them the chance to go to Palestine…”

If in the late 1930s the Soviet security services had tried to portray Hofstein as a Trotskyist affiliated with the Bundists, now they began to position him as the leader of one of two Zionist centers allegedly uncovered in Kyiv. The first, in line with the era’s tropes, was said to involve medical workers and was “headed” by Professor Max Gubergritz. The second – comprised of creative intellectuals – was linked to the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee.

As someone who advocated for the use of Hebrew in the USSR and had once lived in Palestine, David Hofstein was deemed the perfect candidate for the role of leader of the Zionist underground in Kyiv’s literary scene. His connections with foreign writers served as an additional justification for accusations of espionage.

When, in late April 1946, Goldberg, editor of the American newspaper Der Tog, arrived in Kyiv, Hofstein accompanied him everywhere – something that was immediately noted by the MGB. They claimed Hofstein had presented Goldberg with a biased picture of the campaign against Jewish culture and had made frequent Zionist remarks. The security officers were also interested in Hofstein’s meeting with Paul Novick, editor of the Jewish newspaper Morgen Freiheit.

In the spring of 1947, during a creative trip to Chernivtsi, David Naumovich made the ill-advised remark that there were many antisemites in Soviet institutions, and he criticized the exile of Jewish people to Birobidzhan. “What do you have in Birobidzhan anyway? A wheel rim factory?” the Jewish writer asked. “In Palestine – there’s industry and a flourishing culture.” Those present were shocked into silence. One local teacher warned that such words could easily land someone in prison. His words would prove prophetic…

After the arrests of numerous Kyiv intellectuals, Hofstein was not afraid to petition high-ranking officials for a reduction in their sentences. But on September 16, 1948, based on the materials of the 5th Directorate of the MGB of the Ukrainian SSR, Hofstein himself was arrested. He would have been arrested earlier, but the elderly man was gravely ill and spent weeks bedridden. As soon as he showed signs of recovery, he was taken away. Hofstein became one of the first people arrested in connection with the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee case.

David Naumovich was no stranger to the Soviet justice system. Back in 1939, he had been involved as an expert witness – alongside Grigory Polyanker – in the case against Moyshe Pinchevsky, a Jewish poet and playwright accused of espionage. Hofstein understood all too well what he was facing: a ruthless machine that would grind a person to dust – guilty or not.

The very next day after his arrest, on September 17, 1948, Hofstein admitted that due to his religious upbringing, he had held nationalist views, which had consistently manifested in his writing. The poet was forced to go into detail about his time working in the Education Department of the Ukrainian Central Rada and the Directorate, as well as his ties to members of the Tze’irei Zion movement, many of whom had been repressed as early as the 1920s.

As the MGB investigators had intended, Hofstein confessed to criticizing Soviet national policy – in particular, he confirmed that he had made negative remarks about the closure of Jewish schools. Even the seemingly minor episode in which Jewish writers were denied permission to open a house-museum for the Jewish poet Osher Shvartsman in Korostyshev did not escape the vigilant eyes of the “neighbors” (secret police). Hofstein had been especially outraged by the officials’ refusal. Shvartsman, a revolutionary poet, had been his cousin and had died fighting for the Soviet cause. And now the Soviet state refused to honor his memory because of his ethnicity.

During later interrogations, investigators established that in addition to his connections with members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, Hofstein had regular contact with Jewish religious leaders. In 1944, using his official position, he transferred 46 Hebrew-language prayer books from a special archive to the Jewish religious community in Kyiv. According to the investigation, Hofstein had also regularly received financial aid from “religious figures” associated with America. Initially, this assistance came from Rabbi Shekhtman of Kyiv, and later from the head of the Jewish community in Lviv, named Druz. This aid was, of course, not only for Hofstein himself but also for other Jewish writers in Kyiv who were in dire financial straits.

Hofstein’s Zionist beliefs required no further confirmation. Informants repeatedly recorded the writer’s statements about his devotion to the idea of building a Jewish state in Palestine. Included in the case was a transcript of a conversation between Hofstein and agent Semyonov. The poet explained that Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee leaders Fefer and Mikhoels would never have succeeded in the United States without the support of Chaim Weizmann. (Weizmann, as President of the World Zionist Organization, had enabled the EAK’s successful tour in the U.S. and helped secure Lend-Lease and financial aid for the USSR.)

In July 1945, Hofstein told another acquaintance that he himself had originally been considered for the U.S. trip instead of Fefer, but in the end, he was denied permission to travel: “…They couldn’t send me. After all, I’m someone trying to find a synthesis between Zionism and Communism. I might have first advised one, and then we’d see.” “Zionists are the cream of the Jewish people, the most educated of its cadres,” Hofstein said when commenting on the appointment of prominent Polish Zionist Sommerstein to the Polish State National Council (Krajowa Rada Narodowa).

After the Soviet Union recognized the State of Israel, the poet was overjoyed. In a telegram sent to Beletsky, director of the Institute of Literature at the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Hofstein expressed his hope that Hebrew would soon return to Soviet science and literature as well.

In November 1948, by order of Minister of State Security Abakumov, David Naumovich was transferred to the investigative department for especially important cases of the USSR MGB in Moscow. Just before the transfer, late at night, a warden from the Kyiv prison came to the poet’s wife, Feiga Semyonovna: “Tonight I’m taking your husband, David Hofstein, to a Moscow prison. He’s in good health. He’s asking for a bit of money to buy food for the road… Don’t worry, he’ll be back home soon.”

Even employees of the Soviet penitentiary system, which was in essence inhumane, were moved by respect for this intelligent, elderly Jew. What kind of criminal was he? Clearly, this was a mistake.

But under pressure that not even young and strong men could withstand, David Hofstein was eventually forced to take responsibility for committing outrageous crimes. At an interrogation on June 30, 1949, he stated that, upon returning to Ukraine from Ufa in 1944, he had immediately resumed Jewish nationalist activities. According to him, the orders supposedly came from EAK leaders: Fefer, Mikhoels, and Epstein. This line of confession continued throughout the investigation – for three long years.

One of the investigators, Lieutenant Colonel Lebedev, twisted Hofstein’s testimony to the point that even the organization of a Jewish school in Chernivtsi, where many Yiddish-speaking children lived, was qualified as a heinous anti-state crime. “At first, a small group of Jewish children attended the school, and we made every effort to expand it, to attract as many students as possible…,” Hofstein explained. Lebedev immediately recorded in the interrogation transcript: “In order to raise youth in a nationalist spirit!”

In Moscow’s Lefortovo prison, David Hofstein shared a cell with Lieutenant General Vasily Terentyev, a man close to Marshal Zhukov, and with Marlén Korallov, a young publicist arrested for “attempting to assassinate Stalin.” Korallov recalled that after several weeks in solitary confinement, Hofstein could barely stand on his feet. Nevertheless, gaunt and in a filthy shirt, the poet continued to recite his brilliant verses, offering encouragement to his fellow inmates.

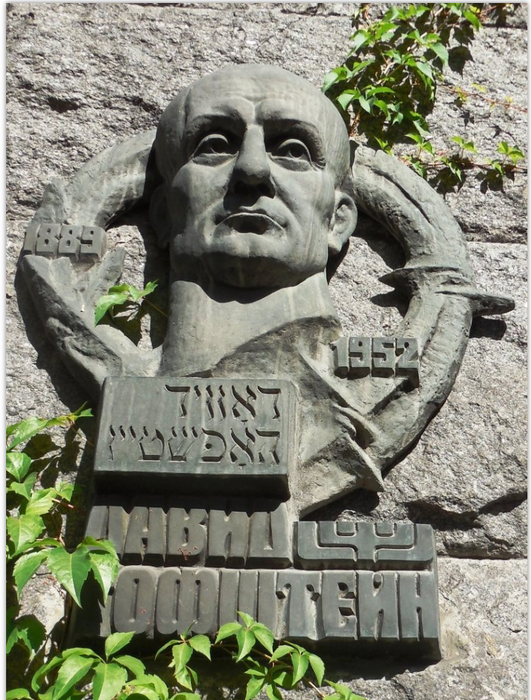

The trial of David Naumovich and other members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC) took place in Moscow from July 11 to 18, 1952. The Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR, in a closed hearing, found Hofstein and 12 other JAC members guilty of crimes under Article 58-1, paragraph “a” of the RSFSR Criminal Code: treason against the Motherland. The sentence: execution by firing squad, with confiscation of all property.

In court, David Naumovich told the presiding judge that during the investigation he was driven nearly insane: “…At that time, during the interrogation, I was in such a state that I simply did not realize what I was signing, what I was doing.”

In his final statement, the poet firmly rejected all accusations: “I have already made a request to the court in addition to the judicial investigation – I want to say that I cannot admit guilt for these charges.”

Testimonies extracted under torture and falsified could not be considered evidence – but this meant nothing to Stalin’s henchmen. They had a clear directive: to destroy the cream of the Jewish national intelligentsia, and any means were deemed acceptable. The sentence against the Jewish poet David Hofstein was carried out on August 12, 1952.

Soon after, the authorities turned their attention to the poet’s family. His wife, Feiga Semyonovna, his daughter Levia, and sons Shamai and Gilel were exiled to Siberia. They returned only three years later. Gilel went on to become a professor of archaeology, Shamai, like his father, took up writing, and Levia, like her great-grandfather, became a renowned violinist.

In 1958, a collection of the executed poet’s verses, translated by Maksym Rylsky, was published in Moscow. Hofstein’s work was republished several more times in the Soviet Union, with Rylsky, his widow Feiga Semyonovna, and his sister Shifra Kholodenko compiling the volumes. In 1997, Hofstein’s writings were published in Jerusalem – the city where he had once participated in the opening of the first Hebrew university, and where Feiga Semyonovna and Levia relocated in 1973. Both Hofstein’s legacy and his family returned to the Holy Land – where the memory of those who fell victim to evil is still preserved.

2025/07/09

Bibliography and Sources:

F.65, File S-6974, Vol. 4: Agent file of the NKVD USSR “Boevtsy” in 2 vols., Vol. 1, 4.11.1938–3.07.1959. – HDA SBU, Kyiv, F.65, File S-6974, Vol. 4 // Project “J-Doc”; accessed July 9, 2025, https://jdoc.org.il/items/show/1840

Review of personal files and decisions of party, trade union, and Komsomol committees of Kyiv for 1950 (alphabetically), 1950. – GAKO, Kyiv, F.P-1, Inv.7, File 67 // Project “J-Doc”; accessed July 9, 2025, https://jdoc.org.il/items/show/741

F.65, File S-6974, Vol. 3: Agent file of the 5th Directorate of the MGB of the Ukrainian SSR, 1st Department, 3rd Section “Krug”, 9.01.1951–22.05.1957, 1977–1982. – HDA SBU, Kyiv, F.65, File S-6974, Vol. 3 // Project “J-Doc”; accessed July 9, 2025, https://jdoc.org.il/items/show/1839

Melamed, E. I. “According to Reports of the Newly Recruited Agent ‘Kant’…” // Archive of Jewish History, Vol. 12, pp. 23–127. April 2022. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781644698846-004

Photo sources:

David Gofshteyn in his youth_source: https://www.lechaim.ru/ARHIV/168/katsis.htm

David Gofshteyn. Selected poems. Cover of the 1937 edition

Jewish writers Joseph Buchbinder, David Bendas and David Gofshteyn (far right), secretly photographed by MGB officers_Agenturnoe delo "Krug" F.65, d

Cenotaph of David Gofshteyn and the grave of his wife Feiga Gofshteyn_source: BillionGraves website

Envelope from a certain Eisenstein family, confiscated from David Gofshteyn_source: Agenturnoe delo "Krug" F.65, d.S-6974

Memorial to the leaders and members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in the USSR, shot on August 12, 1952_source: https://bessmertnybarak.ru/article/noch_kaznennykh_poetov/

Memorial plaque to David Gofshteyn in Kiev_source: https://kiev-foto.info/ru/memorialnye-doski/1147-gofshtejn-david-naumovich

Postcard "Announcement of the creation of the state of Israel", sent from Ramat Gan to David Gofshteyn in November 1948_source: Agent's file "Circle" F.65, d.C-6974

David Hofstein

1889 – 1952