Authors: Anna Nevzlin, Daryna Podgornova

Ida Potik was born in 1921, and her sister Fania in 1922, in the Jewish settlement of Kapreshty, Soroca County — a remote part of Bessarabia, where life moved at a steady pace and neighbors had known each other for generations. Their family was among those who had once relocated there under the initiative of the Tsarist authorities, participating in agricultural colonies, speaking Yiddish, yet able to adapt to a changing world.

The girls’ parents were salaried employees, and the family had five children: Shmuel, Fania, Anya, Rosa, and Ida — the youngest. All the children received their education in a Romanian school and, like many teenagers of that time, searched for identity — they read and discussed news from Palestine. In 1935, Ida and Fania joined the youth organization Gordonia. Their elder brother Shmuel was already an active member — he dreamed of a kibbutz, of communal life, of escaping the dangers of Europe. In 1938, he left for Palestine and settled in Haifa. For Ida and Fania, participation in Gordonia was primarily cultural — they were still too young for the preparatory departure camps and only attended study circles and lectures.

At the beginning of the war, the family managed to evacuate — first to Krasnodar, and after the death of their parents, to Andijan. This saved them from the tragedy that befell many of their fellow countrymen — deportations, ghettos, and executions. However, the evacuation resulted in the loss of their parents, as well as homelessness and poverty. In 1944, they returned — now to Soviet Moldova, to the city of Bălți. Life in Bălți was difficult, as it was for all returnees — there were not enough apartments, food was scarce, and Soviet bureaucracy was stricter and colder than the Romanian system.

The idea of returning to Palestine, which had once seemed distant, became increasingly appealing. Shmuel, by then a well-established community figure in Palestine, sent letters and offered help. But the family was divided: Anya and Rosa were against it; Ida and Fania — in favor. The compromise was a move to Chernivtsi, to live with Anya, who was studying at a medical institute.

In Chernivtsi, Ida worked at the cooperative Vilna Bukovyna. There the sisters lived modestly, corresponded with their brother, and received occasional financial support from him — assistance that would later be interpreted by investigators as “funding from a foreign agent.” Ida reconnected with friends from the Kapreshty Gordonia, in particular with Zina Pripas. In 1948, the sisters discussed a possible departure to Palestine with Beyder and Belinovich, who offered to smuggle them out illegally. However, due to a lack of funds and connections in Romania, Ida and Fania declined. They were waiting for a plan proposed by their brother, which was supposed to be carried out with the help of Shunya Sklyar — head of the Gordonia center in Bucharest. But in January 1948, Shunya was arrested in Bucharest, and that route was shut down.

In the meantime, the Ministry of State Security (MGB) began developing a case against Gordonia as an anti-Soviet organization. To identify and compromise all its members in Chernivtsi, the local MGB office deployed an agent codenamed “Smelaya” (“Brave”), who posed as a member of Beitar and referred to Z.O. Kremer.

In November 1948, she established contact with Froim Miller (a native of Bălți), who intended to leave for Romania illegally. His acquaintance, Iosif Enshelevich Segal, was also interested in emigration. To monitor the attempted border crossing, the MGB assigned another agent to Miller under the codename “Vesyoly” (“Cheerful”). The attempt failed due to a lack of funds, but during the operation, information was obtained about other Gordonia members — including the Potik sisters.

On June 14 of that same year, the MGB arrested Fania first, and shortly afterward — Ida herself. They were accused of participating in the anti-Soviet Zionist organization Gordonia and engaging in anti-state activities.

Their first interrogations took place only a month later. The initial questioning began at 9:30 PM and was conducted by Lieutenant Kovalsky, senior investigator of the MGB investigative department for the Chernivtsi region. At the very start, Fania admitted that in recent weeks, she and her sister had felt they were being followed.

According to the testimonies of other participants, Ida and Fania’s brother, Shmuel, had promised to arrange their escape through Shunya Sklyar. The case was opened against four women: Dvoira Belinovich, Elizaveta Zahaluk, and Ida and Fania Potik. Belinovich was interrogated particularly harshly — her testimony became the basis for implicating 15 suspected participants.

Since Dvoira had long been closely associated with Zelik Weisman and Moisei Yashchikman (who had been responsible for helping Jews cross into Romania in the 1940s), the investigation managed to compile a fairly accurate map of the social network within the Jewish-Zionist movement.

Investigator Kovalsky from the MGB department in Chernivtsi issued an arrest warrant under Article 108 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR. Between June 13 and 16, investigators Kovalsky and Lieutenant Litvin conducted a series of interrogations. The sisters were made to name everyone they had seen, spoken to, or invited for tea. They were accused of “creating an atmosphere of discontent,” “negative comments about the Soviet regime,” and intentions to emigrate. Every word from their private conversations was interpreted as anti-Soviet agitation.

Interrogations often began in the evening and continued late into the night. One of the first sessions started at 11:00 PM and lasted until 3:00 AM; the next began just seven hours later — from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM. Questions were repeated, and if there was even the slightest inconsistency, the sisters were accused of perjury.

The goal of the interrogations was to uncover the entire Zionist network operating in Chernivtsi at the time. Thus, the sisters were forced to recall all their acquaintances and episodes of communication in Chernivtsi.

Starting on July 5, 1949, following interrogations of other participants, arrest warrants, and searches, Lieutenant Litvin, deputy head of the 2nd Department of the MGB for the Chernivtsi region, signed a resolution to place Ida and Fania Potik on the wanted list. On July 7, Major Maltsev and the head of Department “A” of the MGB confirmed that the sisters had been officially declared fugitives. The Potik sisters were considered members of an anti-Soviet Zionist organization and accused of conducting anti-state activities. The MGB department had already obtained a prosecutor’s warrant for their arrest, but the sisters evaded detention and their whereabouts were unknown.

However, by July 13, the head of Department “A,” Dzhus, reported that the sisters had been apprehended. Their time as fugitives had lasted just over a week.

Later, in the presence of official witnesses, a search was conducted in the sisters’ apartment. Seized items included a broken gold watch, a used dress, a jacket, a sundress, new stockings, and several documents — a passport, a work certificate in the name of Ida Yakovlevna Potik, an ID card, and a payment booklet. No books, brochures, leaflets, or notes containing anti-Soviet content were found.

In September 1949, Ida and Fania Potik stood trial. The hearings were held behind closed doors. According to archival materials, they were charged under Article 54-11 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR (“participation in an anti-Soviet organization”) and both were sentenced to 10 years in labor camps. The indictment emphasized their connection to their brother Shmuel, who had previously headed the Gordonia Central Committee in Bucharest and held a post in the Palestinian center — a connection that was used as evidence of foreign coordination.

Their guilt was based on a combination of factors: youthful participation in Gordonia, communication with friends, refusal to inform on others, financial assistance from their brother, correspondence, and cultural conversations about Palestine.

In 1956, after Stalin’s death and the onset of mass amnesties, Ida and Fania were released. The location of their imprisonment is not specified in the case files. It is known that Ida married Shmuel Fish, originally from the town of Stanislav, Galicia. Ultimately, both Ida and Fania managed to overcome Soviet travel restrictions and immigrate to Israel. It is known that both died in Israel — Ida in 2011, and Fania in 1996. Ida Fish Potik is buried in the city of Rehovot, while Faina (Fania) is buried in Tel Aviv.

Yet their story remains a document of an era in which a young woman’s conversation about the future, a letter from a brother, or a student discussion circle could be classified as “hostile activity” — and end in the Gulag.

22.06.2025

Bibliography and sources:

Sectoral State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine, file 16, case 0668

Sectoral State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine, file 1, case 258

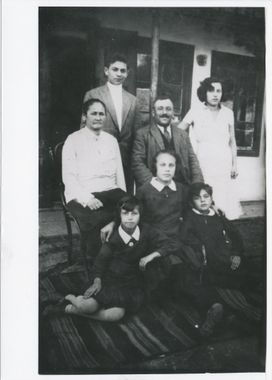

Photographs from the family archive, via the Geni platform

Security Service of Ukraine Archive, Chernivtsi region, case 2843-0

Ida Potik , Fania Potik

1921 – 2011 , 1922 – 1996

.jpg)