Author: Esther-Aziza Sitdikova

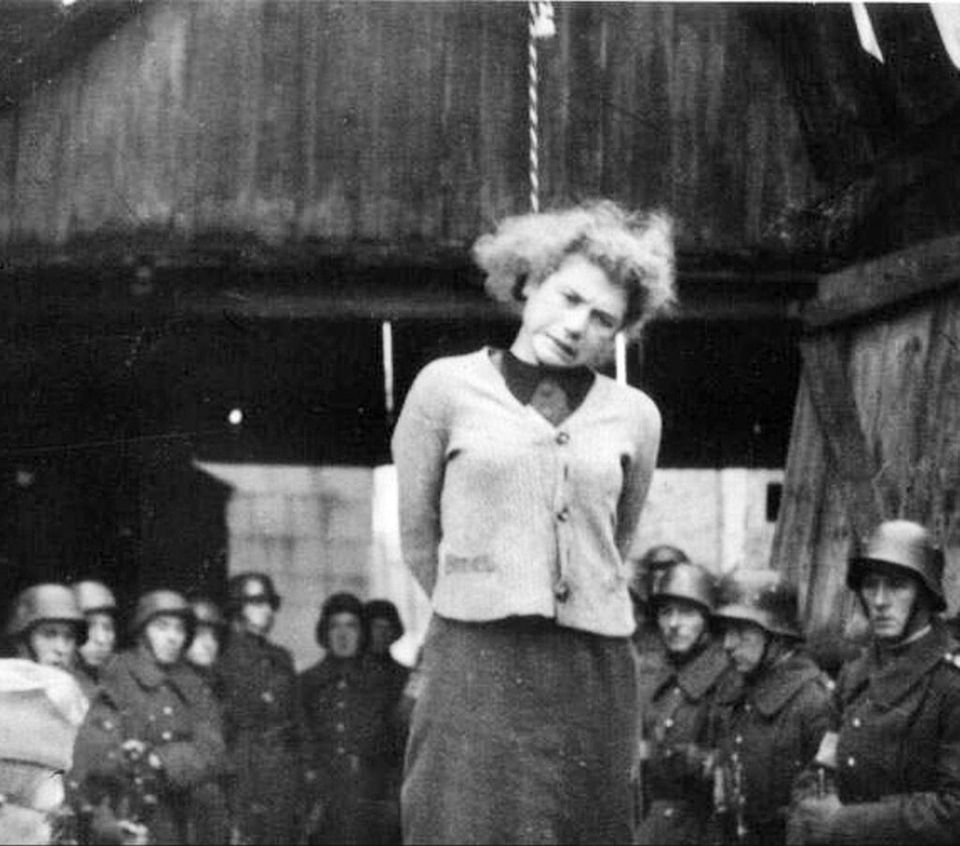

October 26, 1941. The Nazis, who had come to Minsk, decided to stage a show trial – it became the first on the occupied territories of the Soviet Union. If, in the thirties, former allies of the Nazis with crimson-brimmed hats took people out secretly at night, now the murders were put on display. With brazenness and incredible pomp, the Nazis led three underground fighters to their execution. There was only one goal – to intimidate the remaining population of the Belarusian capital and deprive them of their will to resist.

A middle-aged man, a young girl, and a boy were hung from the arch of a bread factory in Minsk. People wondered who the victims were in the huge queue forming at a nearby store. Some said it was a father, son, and daughter; others said they were not related. Most, however, were sure of one thing: Soviet underground fighters had been executed.

In the Soviet film "Executed at 41", released in 1967, the identity of the boy is revealed – Volodya Shcherbatsevich. The film also tells about another man who was hanged – Kirill Trus. His daughter was present during the execution of her father and his comrades, and she saw everything with her own eyes. The filmmakers knew nothing about the young girl who was executed alongside Trus and Shcherbachevich.

But soon, a group of Soviet journalists would discover: the executed girl was 17-year-old Merke Bruskina, a nurse in a prisoner-of-war hospital. Merke, known as Masha to her loved ones, was Jewish. Due to the severance of diplomatic relations with Israel, Communist officials decided that a girl of the "wrong" nationality couldn't be a Soviet heroine. Masha, who is mentioned at the end of the film as an "unknown," will remain so in official historiography for years to come. The obelisk erected at the execution site in 1976 also claims that the girl's name has not been revealed, though this was not true.

Masha Bruskina was born in Minsk in 1924 into the Jewish family of Lia (Lucy) Bugakova and Boris Bruskin. She lived on Proletarskaya Street at first, then her parents moved to Starovilenskaya Street and she was transferred to school No. 28, where she graduated in June 1941.

Classmates remembered her as an excellent actress and an indispensable member of all school performances. She was a true leader and helped her friends with various subjects. Even on a reconnaissance mission, you could trust her! On June 21st, 1940, she had her graduation and the next day, the war started.

Sofya Andreevna Davidovich, a pre-war acquaintance of the Bruskin family, recalled that, almost immediately after the occupation of Minsk by German troops, Masha Bruskina found a job at a hospital for prisoners of war. The hospital was located in the building of the Polytechnic Institute and housed wounded soldiers from the 5th Rifle Corps.

To avoid being discovered, Masha dyed her hair blonde and introduced herself as Bugakova, using her mother's surname. Some researchers believe she also changed her name to Anya, pretending to be a native of Siberia or another region of Russia. As the walls of the ghetto were not yet built, Masha was able to move around the city freely without a yellow star on her clothes. The Bruskins were also forced to destroy some family photos and documents.

Working as a nurse in the hospital, Masha soon began to deliver medicines there. Her mother, Lia Moiseevna, a former employee of the republican book trade department of the BSSR, spent all her free time obtaining fabric and bedding wherever possible, which she used to make bandages. Soviet soldiers were dying from their wounds, but the guards didn't care – the hospital wasn't supplied with either medicine or dressings.

Soon, Masha asked Sofia Davidovich for some men's clothes. As it turned out later, the girl had joined an underground group organized by a 41-year-old man named Kirill Trus. Trus was a worker at a Minsk car repair factory. Together with some other prisoners of war, he decided to rescue Soviet soldiers and transfer them from the hospital to his own people. Every morning, Masha would grab bundles of worn-out trousers and jackets and hurried to the hospital. Unlike her colleagues who carried pots of food from the hospital at the end of their shifts, she refused to steal meager rations from prisoners of war for the sake of secrecy. Although it would have been easier to do what everyone else did, in wartime people often think only of their own families.

One day, Masha timidly asked Sofia Andreevna if she could borrow a camera somewhere. The failure to surrender and possession of photographic equipment in occupied Minsk could be punished by death. But the resistance movement desperately needed a camera. In the early days of the war, prisoners of war were still able to escape from Nazi clutches. However, to successfully escape, not only civilian clothes but also "papers", which patrols checked everywhere, were required. With the aid of a camera, daredevils forged documents. Soon, Bruskina obtained a "Fed" camera purchased by Davidovich prior to the war. This allowed the production of forged documents, thanks to a brave girl. Additionally, according to witnesses, Masha disseminated reports from the Soviet Information Bureau, which she had received from the Truce – they had a radio transmitter hidden in the attic.

Prisoners of war were changed into clothes prepared by Masha Bruskina, received fake documents and made their way from the hospital to the city. Before leaving Minsk, everyone gathered at the apartment of Olga Shcherbatsevich's underground worker, a cultural worker at the 3rd City Hospital, the mother of schoolboy Volodya Scherbatsevitch, who was executed along with Masha later. The apartment was located on Kommunisticheskaia Street. Some were hidden at Olga's sister Nadezhda Yushkevitch, Minsk residents Anna Makeychick and Elena Ostrova, as well as other city residents. There they ate, rested, and waited for transportation. One group was even taken out of the city comfortably in an old truck. Most prisoners of war later joined partisan units or went to the front lines. It is believed that the brave men managed to rescue 48 people during the operations of the underground unit.

But the period of relative calm ended soon. One of the leaders of the underground, a Soviet commander named Volodya, ordered Masha not to come to the hospital anymore. It is unknown whether the underground feared that someone would eventually recognize the girl as a Jew and immediately turn her in, or whether they were going to go to their own people. Masha Bruskina no longer appeared at work in early October 1941.

Several groups of fugitives left Minsk at once in early October. Boris Rudzyanko was among them. He was a technical quartermaster of the second rank who had been rescued from a prison camp. The group stumbled upon a patrol and was taken back to Minsk. Rudzyanko betrayed all members of the resistance known to him during the first interrogation and subsequently went to work for the Germans.

The Nazis captured Masha Bruskina on October 14, 1941. The girl was sitting at home when two young men suddenly appeared in the yard. They asked the children in the yard if Masha, the blonde, lived there. Hearing that she was being sought through the open window, the girl looked out and said that she would go with them. Running out of the house, she shouted to her mother that the guys had come and that she'd be back soon.

As children who ran after Bruskin and the strangers told later, two armed Germans approached them right outside the gates of the ghetto. Her companions did not fight the soldiers, but took police armbands out of their pockets and tied them on each other's arms.

Masha ended up in prison. Lia Moiseevna was beside herself. By a miracle, a policeman turned up who agreed to take a bribe to bring her daughter a parcel to prison. The girl's mother soon received a note with roughly the following text: "Dear Mommy! Most of all, I am tormented by the thought that I have caused you great concern. Don't worry. Nothing bad has happened to me. I swear to you that you will not have any other troubles because of me. If you can, please send me my dress, a green blouse and white socks. I want to look good when I get out..."

Lia Moiseyevna and her friend and colleague, Sofia Davidovich, were horrified. They realized that Masha had hinted that she had undergone torture and had not defamed anyone. And why was there such a festive look on her face - clearly not just for getting out of prison... The women packed Masha's autumn boots and her favorite dress into the parcel. In exchange for bringing the bundle, the police officer received Liya's watch.

On that fateful day, October 26, 1941, twelve previously captured Minsk underground fighters were taken out of prison. The condemned were divided into four groups and led to different places: to the Komarovka area, to the intersection of Komsomolskaya and Marx streets, to the square near the Officers' House, and to the yeast factory on Voroshilov Street (now Oktyabrskaya).

Soldiers of the 2nd Battalion of the Lithuanian Auxiliary Police Service, under the command of Major Antanas Impulavicius, and their German masters, brought out plywood boards and hung them around the necks of some underground fighters. The boards had inscriptions in Russian and German, saying "We are partisans who fired at German troops", although none of them had fired a shot at the occupying forces. These people were saving prisoners of war who were doomed to painful death from hunger, typhoid, and beatings in German camps.

Masha and two other comrades were taken through the city center to the yeast factory before the execution. Before the killing, an SS officer delivered a speech emphasizing that such a fate would await anyone who resisted the new order. Executioners filmed the executions in detail, hoping to break the will of the subjugated people to resist the Nazis by distributing photos.

The occupiers wanted the victims to face the crowd during the execution. But Masha Bruskina, standing on a stool, defiantly turned her back on the fence. The executioner approached and kicked the chair out from under her feet. Masha was hung first. Then, Volodya Shcherbatsevich and, lastly, Kirill Trus were hanged.

In the evening, news reached the ghetto that Masha had been killed. Lia Moiseevna was restrained by force when a neighbor came to visit her the next day. When the neighbor spoke, Lia did not respond; she just circled around in front of a mirror as if dancing. Her mind could not cope with the loss. She did not live long after her daughter's death. On November 7th, 1941 (the day of the famous parade on Red Square), Lia Bugakova was killed during the pogrom in the Minsk Ghetto.

The bodies of the underground fighters were removed only on the third day. At half past three, a car arrived at the yeast factory. A German officer brought with him two Jews with stars sewn on their clothes. Standing on the same stools, the Jews cut the black and white ropes and loaded the bodies into the back of the truck. The location of the graves of Masha Bruskina and others executed that day is unknown.

On August 11, 1944, the newspaper "Komsomolskaya Pravda" published two photographs discovered, as stated in the accompanying text, by Soviet soldiers during the liberation of Minsk. The photographs captured the execution by hanging of an unknown man, a young man, and a girl. The photographs were handed over to the Soviet command by a Minsk photographer.

During the occupation years, the photo studio of Volksdeutscher Boris Werner operated in Minsk. Alexey Kozlovsky, who worked for Werner, made duplicates of photos that captured the atrocities of Nazis. He hid those photos, including those of Masha and her friends, in a tin can in the basement.

After the war, photos from the series were found in Lithuania among the belongings of dead German soldiers and once in an abandoned house.

Photos of Masha Bruskina and other fighters executed in Minsk were used as evidence at the Nuremberg trials.

In 1968, journalists Vladimir Freidin, Lev Arkadiev, and Ada Dikhtyar collected testimonies from people who knew Masha. The girl was identified by her neighbor on Starovilenskaya Street in Minsk – Vera Bank. She described her clothes in detail and told how the girl went to work in a hospital for Soviet prisoners of war. Her former classmates, including her desk mate, also recognized her immediately. The former director of Minsk School No. 28, Natan Stelman also unequivocally stated that this was his school's graduate, Masha Bruskina. And most importantly, the father of the girl, Boris Davidovich Bruskin and her cousin, People's artist of the USSR, Zair Isaakovich Azgur were found.

However, it was a matter of politics. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union refused to recognize the executed heroine as a Jew. Pressure was put on Vladimir Freiden, and Lev Arkadiev and Ada Dickhtyar were fired from their jobs and their version was declared incorrect.

For many years, the authorities pretended that the name of the executed girl was unknown. Ideologists even put forward counter-versions, completely ignoring irrefutable evidence. Only in 2008 did official Minsk finally acknowledge that the researchers were right, that the photograph depicted Masha Bruskina, a graduate of Minsk School No. 28. On July 1, 2009, a new memorial sign was unveiled at the entrance to the Minsk Yeast Factory, on the site where Bruskina and her companions were executed. Now, her name is included on the sign.

This tragic story had another sad continuation. When the traveling exhibition "Crimes of the Wehrmacht. 1941-1944" arrived in Munich in the spring of 1997, a local journalist, Annegrit Eichhorn, came to cover it. Suddenly, the woman became unwell – she saw her father, a German officer, on the gallows in a photo. He died on the Eastern Front in 1943. However, his daughter always believed that he had been a soldier and not a punisher, as a result of his work as a journalist before the war. The journalist wrote an emotional article, but soon began to be harassed by far-right radicals, who did not like her condemnation of her father's Nazi past. Unable to cope with emotional turmoil, Annegit committed suicide.

Masha Bruskina was only 17 years old when her life was tragically cut short. Despite her age, she selflessly helped those in need, refusing to submit to her executioners even on the scaffold. The people of Minsk will always remember their courageous fellow countrywoman. Heroes live forever.

04.06.2024

Bibliography and sources:

Lessons of the Holocaust: History and Modernity. "The Case of Masha Bruskina" / Compiled and edited by Ya. Z. Basin. — Minsk: Kovcheg, 2009. — Vol. 2. — 216 p.

A. Torpusman. A New Execution of a Jewish Partisan // Journal "IsraGeo". 21.02.2016

The Known "Unknown". Collection of materials. Compiled and edited by Basin, Yakov Zinovievich. Minsk, 2007. — 138 p.

Executed in Forty-One (1967). USSR, Minsk Studio of Popular Science and Chronicle-Documentary Films, 1967.

Masha Bruskina

1924 – 1941

_03_edited.jpg)