In 2019, an unusual ultra-marathon took place in the Tatras. Israeli Rani Geva ran 70 kilometers in the mountainous terrain between Poland and Slovakia. The athlete chose the route for a reason - in about the same way during the Second World War, his grandfather, Uziel Lichtenberg, fled from Poland, captured by the Nazis, to Slovakia. He later used the same route to ferry groups of Polish Jews from Nazi hell.

Jewish hero, Uziel Lichtenberg, was born on February 1, 1916 in the Polish town of Zhuromin into the family of an entrepreneur, chairman of the local Jewish community Shlomo Lichtenberg and housewife Rivka-Brakha Korel. In 1930, the family moved to a large industrial center located 120 kilometers from Warsaw-Lodz.

Having moved to Lodz with his parents, 14-year-old Uziel fell into an atmosphere of freethinking. There were Jews in the big city, who broke with the Hasidic courts a long time ago, and already looked more like Poles than like their God-fearing fellow tribesmen. Uziel's father was also a progressive man. Back in Zhuromin, he enrolled his son in a Polish primary school, having performed an act that was rather extravagant according to local perceptions. The family had to compromise: after studying, Uziel went to his grandfather to learn the Talmud.

Due to financial problems in the family, the boy had to grow up very quickly. Seeing how his father was striving, he himself decided to go to nearby shops in search of work. After settling in a shop as a bellhop, Uziel began to bring home the bacon.

Soon, the smart guy was noticed, and he began to work in the construction company of Herman Kalisz, where, after graduating from high school and a two-year evening training course for construction technicians, he received a promotion.

From the very beginning, the young guy worked in a Polish environment: he, the owner of the company, engineer Kalisz, and his secretary were the only Jews at the company. He adhered to his Jewishness, but understood it, in contrast to his father, in a different way. Constantly working with his colleagues on Shabbat, without paying any attention to prejudice, Lichtenberg leaned towards secular, working-class Zionism. By that time, his two older sisters had already left for Palestine, and he himself enrolled in 1932 in the “HaNoar HaTzioni” – a centrist youth movement that fought against the Bundists.

Spending time after work at the headquarters of the organization, Uziel soon became the head of the Lodz cell – “kena” – and a member of the central council of “HaNoar HaTzioni” in Poland. His task was to teach young people who were going to leave for Eretz Israel upon reaching the age of majority.

In 1935, Uziel met his future wife, Bluma Fried, a high school student, just like him, a fan of Polish poetry and an ardent Zionist. The young people dreamed of going to Palestine together, but, as a citizen of Poland, Lichtenberg decided to first serve in the army. Moreover, service in the armed forces was promoted by all Zionists, from right to left, reasonably believing that military skills will still be useful to repatriates.

On February 1, 1938, Lichtenberg began service with the artillery regiment in Skierniewice, between Lodz and Warsaw. The commander doted on the clever enlist and sent Uziel to the officer's courses, which he graduated exactly on the eve of the war, on August 31, 1939.

Uziel was terribly worried about his parents and his beloved, Bluma, who was in the “kibbutz-akhshara” near Warsaw, where she tirelessly prepared for agricultural work in the Promised Land. World War II had broken out five days before her alleged aliyah, and it was now unknown what happened to her and her brother.

Together with his fellow soldiers, the young officer was taken prisoner by the Germans. Polish soldiers were stationed at Stalag II-A in Neubrandenburg. A stab in the back awaited the Jews in the camp: the Poles demanded that the Germans place the Jewish prisoners in separate tents. Soon there was a very disgusting incident. Uziel stood in line for food, but someone unexpectedly kicked him and pushed him aside. A German soldier guarding the prisoners asked the Pole why he did it. “Jude”, – he answered with a grin. The guard's reaction was unexpected. “Yesterday he was your comrade, but today he is a jude?!” – shouted the German and punched the Pole in the face.

Uziel cried like a child that day. He was ashamed and painfully offended that the German, the enemy, was protecting him from his own fellow soldier. Lichtenberg was a Zionist, advocated the construction of a Jewish state in Palestine, but he was completely loyal to Poland. His ancestors were born in Poland, he was born himself, but even in such conditions, some Poles did not deny themselves the pleasure of showing him in his place.

In February 1940, Uziel, as a Jew, was sent to a labor camp in Lublin. Ukrainian guards were assigned to the prisoners, who could shoot anyone for no reason. But one day, when the prisoners were cleaning the streets of the city, Uziel managed to escape. He was lucky enough to get in touch with local Zionists, who procured clothes for the fugitive and gave money for the train.

Returning to Lodz, the former prisoner of war immediately went home. At the apartment he was met by a frightened father, who advised him to leave immediately: the Gestapo found Uziel's name in the lists of Jewish leaders who had supported the boycott of German trade before the war, and were actively looking for him in the city.

From Lodz, Uziel decided to go to Warsaw. The fugitive first walked to Warsaw on the country roads, which he and the members of “HaNoar HaTzioni” had walked to their hearts' content before the war. He managed to travel part of the way by train. In the city, the young man decided to find the leadership of the Zionist youth, which was located at 49 Zamenhof Street. There was no leadership, but the former members of the organization held onto each other and tried to live in one place, forming a kind of kibbutz. There, Uziel met his Bluma, which he had not heard of for many months. The couple decided to stay together in the kibbutz, even without the wedding, which was postponed until aliyah. The kibbutz procured food for its members; Uziel had a room for a general overnight stay, and even took Hebrew lessons there after work. Lichtenberg and several of his friends managed to negotiate jobs for their comrades - it was impossible to survive without work in the ghetto. The members of the kibbutz were the first to work at the famous brush-making factory located on Leszno Street.

In those days, Jews were still allowed to farm. From May to October 1940, Uziel and Bluma were on a farm in Grochow, near Warsaw, where the most famous center for agricultural training of future repatriates was located before the war. Through cultural and educational activities on the territory of the kibbutz, members of various youth organizations hoped to counteract the demoralization of the Jewish community. And the stocks of food produced in the fields of the farm came in handy for the hungry in the ghetto.

The beginning was very difficult, as the entire infrastructure was destroyed during the hostilities. However, thanks to pressure on the Judenrat, as well as selfless work, the kibbutz was restored.

Even before the closure of the Warsaw ghetto, at the end of 1940, unexpected news reached Uziel and Bluma. One of their acquaintances was going to Eretz Yisrael! Lichtenberg couldn't believe what he was hearing: people were being transported from occupied Europe to Palestine. At the border, some kind of secret “apparatus” was formed, which was engaged in the transfer of refugees. The route was simple: Slovakia, Hungary, to the Danube, from there – to English territory, to Palestine. Each movement could transport a certain number of people, according to the quota, and “HaNoar HaTzioni” received one seat, which the members of “HeHalutz” gave up to the movement.

When, at the end of February 1941, Uziel was asked to participate in the organization of the “brihi” (an underground organization engaged in the export of Jews from besieged Europe), he immediately agreed. As one of the leaders of the Zionist youth, he was given a responsible task - to find ways and facilitate the illegal transfer of Polish Jews to Slovakia.

They left Warsaw together with a guide, as well as an activist of Hashomer Hatzair, Rut Shmulevich. At 8 o'clock in the evening, the trio began a difficult climb to the Tatras, which lasted until the morning. The next day, the travelers were already walking through the mountains. According to the guide, no one patrolled the mountain trails, and there was no need to be afraid of sudden ambushes. But in the morning, having spent one more night on the way, the fugitives saw the light of lanterns in the distance. Having successfully passed the Slovak border guards, the trio was able to descend to the foot of the mountain near the town of Poprad in a few hours. There they were met by a local peasant who brought Uziel and Ruth to a Jewish family helping refugees.

In Bratislava, the Friedel family was the liaison officer for the Warsaw Coordination Committee, which sent Lichtenberg and his companion across the border. Having reached the capital of Slovakia by train under the guise of tourists from Germany, Uziel Lichtenberg and Ruth Shmulevich had to come to the apartment of the messengers. However, finding an address in an unfamiliar city proved to be difficult. A firefighter who spoke German well came to the rescue. On the threshold of the apartment “German tourists” and their assistant saw an elderly woman. The hostess decidedly did not expect any guests, let alone from Germany. It was only when the firefighter left that the already desperate Uziel received a scolding from Mrs Friedel: mistaking a Slovak policeman for a firefighter is a serious puncture.

In Bratislava, Ruth and Uziel said goodbye: the girl remained in the Hashomer Hatzair commune, and Lichtenberg joined the Maccabi Hatzair movement, which instructed him to deal with fugitives from Poland who were going to repatriate to Palestine. Uziel became a liaison between Warsaw and Bratislava. The legal cover for this activity was the “Ustrednya Zhidov” – “English Jewish Center”, the Bratislava Judenrat, which was headed by famous Zionist leaders in Slovakia.

Thanks to the energy of Lichtenberg, an entire underground network was created to transport refugees. On the Slovak side of the border, in the town of Bardejov, worked Shlomo Tsagelnik, who met Polish Jews in the forest and gave them lodging for the night in a safe house. Then the fugitives got to Presov, 50 kilometers to the south. In Presov, Lichtenberg rented exactly the same safe house in his own name, taking people from there and transporting them further to safer places.

In April 1941, Lichtenberg, as a person with extensive organizational experience, began to set up an agricultural “akhshara” in Slovakia. This position provided for a salary, a place to sleep, and, most importantly, it provided a legal opportunity to employ fugitive Polish Jews to work in agriculture by agreement with local farmers. Aliyah from Slovakia soon ceased, but Lichtenberg continued to welcome people to whom even this country with powerful anti-Jewish legislation seemed like paradise compared to occupied Poland.

On June 22, 1941, on the day the war between the USSR and Germany began, Lichtenberg's bride also managed to cross the Polish-Slovak border. Relative calm lasted until the end of December 1941, when rumors spread across Slovakia about the imminent eviction of local Jews to labor camps. Understanding well what this is fraught with, Lichtenberg and other immigrants from Poland persuaded the Slovak Zionist leadership to organize the evacuation of people. They knew from experience that the so-called labor camps are nothing more than death camps.

When the authorities began to expel Jews from Slovakia in March 1942, Uziel Lichtenberg and Bluma Frid, as part of a group of Zionists, illegally crossed the border into Hungary.

In Hungary, through the efforts of the regent Miklos Horthy, a tough police regime was established, so it was almost impossible for foreigners to remain unnoticed. All public organizations were under vigilant control, in every house there was a guard connected with the police, and without a registration it was simply forbidden to be in the cities. A significant part of Hungarian Jews were wary of the Zionists, and even more so of the foreign Zionists. They had to rely only on members of the local youth movement Maccabi, who settled their Polish comrades-in-arms in their parents' apartments for a couple of days, and then helped them with legalization.

Under the guise of a couple from the Carpathian Rus, occupied by Hungary, the Polish messengers got a job. Immediately, they actively set about creating the “Inter-Organization Committee on Refugees” being responsible there for helping the members of the Maccabi organization.

In June 1942, Uziel Lichtenberg and Bluma Frid were looked for. It was not safe to stay in the city, so after changing several apartments, Lichtenberg decided to buy passports from the Romanian embassy. There was an official who, for a certain fee, helped Jews to become Romanian citizens. Newly made “Romanians” could go to third countries, from where there was no extradition.

Having passed the advance payment and after some time came to a meeting with an official at a posh restaurant, Uziel was detained by Hungarian counterintelligence officers. Lichtenberg was taken in a black car straight to the military prison of Hodik. Soon, Bluma was taken there, captured in a safe house.

The interrogations began the next day and lasted until the evening. For some reason, Germans were in charge instead of Hungarians. Six weeks later, having come to the conclusion that they were dealing with ordinary refugees, and not members of a Polish military organization or paratroopers from Moscow, the court's decision was to release for lack of corpus delicti. However, the refugees were not released, but transferred to a prison where illegal migrants were kept. A month later, the couple was deported to the Rombach camp, which held refugees awaiting deportation.

Together with three dozen Slovaks, the underground workers were soon taken to the border. However, at the border crossing in the area of the Danube Canal, the Slovak border guards refused to let Polish citizens into their territory. After waiting until morning, the refugees went back through the forest paths, but fell into the hands of the border guards, who again sent them to the neighboring country. This carousel on the Hungarian-Slovak border lasted 17 days, until one of the pitying Hungarian border guards told Lichtenberg that in Hungary you can count on a prison as border violators if you go 15 kilometers deep into the territory. Otherwise – again deportation to Slovakia.

And so they did. Then there was the same prison in Budapest. Lichtenberg was assigned to work in a carpentry workshop, but already in October 1942 the unexpected happened: together with all the Jews under the age of 40, Lichtenberg was sent to the east as part of a “labor battalion”.

The only benefit of the criminal order was that Bluma, as the “wife of a Hungarian soldier”, was released from prison and sent to a refugee camp on Szabolcs Street in Budapest. There she accidentally learned that a youth aliyah was going to Eretz Israel, and in February 1943, using forged documents, was able to leave Hungary for Palestine. Uziel was happy: at least his beloved managed to escape and realize the aliyah planned before the war.

In the labor battalion, Lichtenberg and his friend, the Polish Zionist Arthur Reichert, decided to write reports that in fact they were ethnic Poles and Christians. While the proceedings were going on, their battalion was sent to the eastern front, deep into the Soviet Union. The “Christians” were sent to a camp for displaced persons on Magdolna Street in Budapest.

It is not known how the fate of the two Jews would have turned out, but during the visit to Garen of the famous patron of the arts, Baroness Roja Weiss, Uziel and Arthur managed to agree that she would put in a good word for them, “Christians” from Poland. The aristocrat kept her word, and soon the illegal immigrants were transferred to the Riche camp in the Carpathian region.

On October 19, 1943, Jewish refugees were unexpectedly returned from Riche to Budapest. The war was moving towards a turning point, and the reason was political – the Hungarians were trying to show the anti-Hitler coalition that the Hungarian government had nothing against the Jews.

After being transferred to Budapest, Uziel managed to get a recommendation from the “Civil Committee for the Protection of Polish Refugees” and get a job there, as a former Polish officer. In the Ministry of Internal Affairs, their people got hold of new documents for Uziel – in the name of a Christian Pole.

While Uziel was in the camps, refugees from Poland, primarily from Silesia, began to arrive in Budapest. The young man, who had already established himself as a savior of the Jews, was admitted to the Budapest Committee for Aid and Rescue.

The underground worker was instructed to get Christian documents for the wards, Polish refugees, and to look for temporary housing. Having compiled lists of newcomers to Budapest, Uziel sent them to Tel Aviv, where he asked to find out which of them could be sent certificates of entry to Palestine. The lucky ones left for Eretz Israel, while the rest of the representatives of the Yishuv and the Zionist leadership, who were in Istanbul, received financial assistance.

Lichtenberg also tried to accommodate those refugees who did not have any contacts in Zionist circles, were not members of movements and, accordingly, did not know who and where to turn to in Budapest.

In addition to providing assistance on the spot to those who had escaped from Poland on their own, the Budapest Zionists hired messengers who tried to find survived Jews in Poland and, if possible, take them out to Hungary.

In December 1943, the Zionist underground in Hungary began to work out options in case of the occupation of the country by German troops. The leadership of the “Budapest Committee for Relief and Rescue” decided to urgently evacuate from the country the employees who had already become familiar with the Hungarian counterintelligence. Among them was Uziel Lichtenberg, who on February 19, 1944, together with 14 other activists of the Zionist movement, disguised as a Hungarian journalist, left Budapest by train. While the group was advancing to Istanbul, German units entered the capital of Hungary.

The refugees from Turkey soon found their way to the territory of the Mandatory Palestine. At the kibbutz Nitzanim Uziel met after nearly two years of separation from Bluma. The wedding was played without delay.

In Eretz Israel Lichtenberg, together with Golda Meir, traveled around the country and talked about the tragedy of European Jewry, which he saw with his own eyes.

After repatriation, he learned that his parents were sent to Auschwitz in August 1944, where they were martyred in a gas chamber.

After the end of the Israeli War of Independence, in which Uziel and Bluma took an active part, the Lichtenbergs settled with two small children in the poor Tel Aviv quarter of Shhunat Shapiro. In 1950, Uziel returned to his pre-war profession, subsequently opening a construction company in Tel Aviv. He was also engaged in social activities, becoming an activist of the Histadrut and one of the founders of the Center for the Study of the History of the Holocaust “Masua” in Kibbutz Tel Yitzhak.

Until the end of his days, he adhered to left-Zionist views, harshly criticizing the right-wing agenda and religious parties.

To frequent reproaches that Yishuv did little to save European Jewry, Uziel replied sharply: “He did exactly as much as he could under those conditions, and even more”.

Uziel Lichtenberg passed away on February 11, 2018. He is buried in the Kiryat Shaul cemetery in Tel Aviv. His daughter, Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger, is a renowned artist and feminist activist.

Granddaughter Lena Ettinger is a popular film actress. Grandson Rani, with whom our story began, is a healer and physiotherapist. He also regarded his run through the places of glory of his grandfather as an act of psychotherapy: returning to traumatic places with positive thinking can help heal wounds, return to family roots, and close the loop of history. “It seemed to me that I was running in the darkness with a torch and illuminating this darkness, bringing life into it ”.

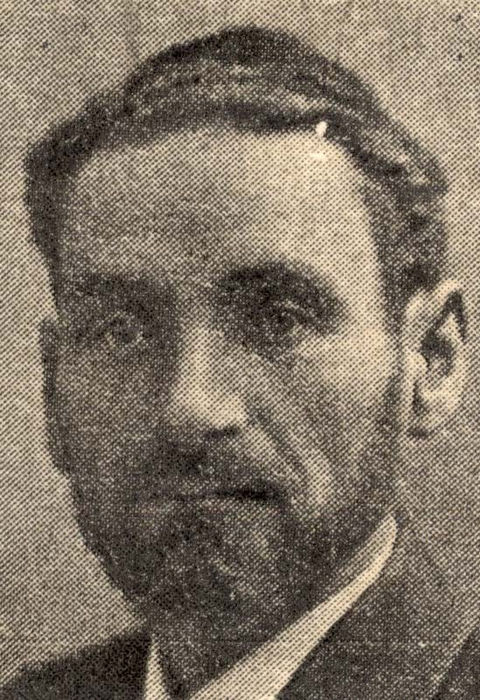

Uziel Lichtenberg

1916 – 2018