A special message dated May 26, 1949, sent by the Minister of State Security of the Ukrainian SSR, Lieutenant General Savchenko, to Moscow, spoke of the liquidation of the Zionist youth organization “Eynikayt” in Ukraine. The high-ranking official reported that the implementation of the undercover operation "Writers" was nearing completion, and new arrests had been made in local educational institutions. Among the arrested was a student of the Vinnytsia Medical Institute, Meir Gelfond. The investigation revealed that Meir Gelfond (referred to as Max Borisovich Gelfond in the document) and his friends, all originally from a village near Zhmerinka, had agreed to disperse to various cities of the Soviet Union after finishing school and, in the language of Soviet documents, continue "nationalist work to organize anti-Soviet underground activities" in higher educational institutions.

The medical student Meir Gelfond, arrested in March 1949, indeed did not harbor any affection for Soviet authority. However, he didn't plan to overthrow the Bolsheviks; his goal was the distant land of Eretz-Israel. It was for the homeland of the Jewish people that he had to endure numerous trials generously scattered along his path.

Meir Gelfond was born on June 24, 1929, in the village of Mezhyriv near Zhmerinka, in the Vinnytsia region of Ukraine. His father, Berko Yankelevich, worked as an accountant, and his mother, Sara Meirovna, was a housewife, raising Meir and his sister Lea. The Gelfond family was not explicitly religious, but from early childhood, Meir celebrated Jewish holidays and communicated exclusively in Yiddish at home. The environment also contributed to this. In the Jewish school in Zhmerinka, where Meir Gelfond studied before the war, the atmosphere was, as they liked to say then, Soviet in content, but national in form. There was only one non-Jewish student in their class, a Ukrainian named Petro, whom everyone called Pinchik. Pinchik assimilated so well into the Jewish environment that he spoke Yiddish as well as his classmates. This was true for the rest of the students who preferred Sholem Aleichem over Pushkin.

When the Soviet-German war broke out, the Gelfonds managed to evacuate from Zhmerinka to the Southern Urals. For three years, Meir, along with his parents and sister, lived and worked in a remote collective farm, and at the end of 1944, the family returned home. To their surprise, in Zhmerinka, the returning refugees discovered not only household anti-Semitism but also an extremely negative attitude towards Jews from local authorities. Arrogant officials barely concealed their reluctance to grant registration to those returning from evacuation because of the "incorrect" nationality of the applicants.

There was no longer a Jewish school in Zhmerinka, so Meir and his friends had to continue their education at the local Russian School No. 2. Disturbed by the dire situation of the Jewish population, at the end of 1944, Meir and his classmates Vladimir Kertzman, Mikhail Spivak, and Alexander Khodorkovsky decided to unite in an underground organization called "Eynikayt" (translated from Yiddish as "Unity"). The young Zionists aimed to return all Soviet Jews to Eretz-Israel, where they could build a modern state that would protect them from any danger.

The young people knew very little about Palestine, only what was taught in history classes. They had never heard of figures like Theodor Herzl and David Ben-Gurion, imagining themselves as pioneers of an entirely new revolutionary movement for the Jewish people. Gradually, individuals such as Tatiana Khorol, Klara Shpigelman, Alexander Sukher, Moisey Geisman, David Gervis, Ilya Mishpotman, and Yefim Volf joined the core of the organization.

The students' first "operation" was distributing handwritten leaflets during the Simchat Torah holiday at the local synagogue. In these homemade leaflets, the young people urged Jews to go to Eretz-Israel. However, this action received no response, neither from the remaining Jewish residents of Zhmerinka nor from refugees from Poland and Romania. People were terribly afraid of attracting the attention of the MGB (Ministry of State Security), which closely monitored its citizens.

When the young underground activists approached the local rabbi with inquiries about Palestine, he immediately dismissed them. The young conspirators had high hopes for contact with a young woman who had been a member of the Zionist party in Romania before the war. The girl, now living in a neighboring village with Ukrainian peasants who had saved her during the occupation, warmly welcomed Gelfond and his friends but said she could not help them as she no longer maintained any contacts with the Zionists.

They decided to spread their messages in other cities. Their leaflets in Yiddish and Russian appeared in Vinnytsia and Kyiv. The members of "Eynikayt" also managed to engage in individual conversations with people on Jewish topics. Sometimes, the members of "Eynikayt" would meet directly on the streets of Zhmerinka, and at times, at the apartments of Mikhail Spivak and Tanya Khorol, where they discussed the organization's affairs and exchanged important information.

In 1946, the initiative with leaflets dwindled, but the young underground activists decided to seriously focus on Jewish self-education. While they all spoke Yiddish, only some in the group could read and write in Yiddish. There was no discussion of Hebrew at that time. This unique "ulpan" existed until 1947 when the members of "Eynikayt" entered universities in different cities across the country.

In 1947, Meir Gelfond became a student at the Vinnytsia Medical Institute. To the surprise of the first-year student, a national upsurge began to be felt in Vinnytsia. The city actively disseminated works telling the difficult fate of Jews. Margarita Aliger's poem "We are Jews" and the equally famous poetic response from the frontline poet Mikhail Rishkovan were particularly popular. When people learned about the struggle for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine from Soviet media and Western radio stations, the youth began preparing to move to the Middle East. In the Vinnytsia Medical Institute, Jewish students actively engaged in physical education and studied martial arts, believing it would be useful for the defense of the Jewish state.

Despite the widespread enthusiasm, by the summer of 1948, Meir Gelfond came to realize that the "romance" between the Soviet Union and the state of Israel was a fiction, linked only to the Kremlin's foreign policy ambitions. With every fiber of his being, he felt that Soviet Jewry was on the verge of significant upheavals. In the fall of 1948, all his fears began to be confirmed. In the USSR, the last Jewish schools, theaters, and writer unions were closed. By the decision of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was disbanded, and its members were arrested. One by one, former members of "Eynikayt" also found themselves behind bars.

Early in the morning on March 24, 1949, a knock came to the door of the apartment where Meir Gelfond and his fellow student shared lodgings. Two strangers in plain clothes stood at the threshold, requesting permission to enter the apartment. The men, who turned out to be Vinnytsia UMGB (Ministry of State Security) officers, conducted a thorough search. Confiscating notes and books, the security officers took Gelfond to the local MGB prison.

The security officers couldn't believe that students from Zhmerinka were acting independently. Eli Spivak, a Yiddish scholar and a member of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, arrested in connection with the case of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, was "appointed" by MGB employees as the ideological inspirer of the youth. He was a distant relative of Misha Spivak, whose testimony the security officers were desperately trying to obtain. Eli Spivak had no connection to the youth, but investigator Goryun needed only his signature on the protocol. Thus, a forged farewell from Spivak, allegedly addressed to the youth of Zhmerinka, became part of the case: "This depends on you, youth. Act, and we will support you."

Meir was fortunate with the neighbors in the first cell. Some were "repeat offenders," individuals arrested a second time for an old case. One of them was the poet Eydlin, who recited poems to fellow inmates and organized lectures. Meir joined the self-education circle, sharing his knowledge of physiology, which he was passionate about at the medical institute. After a month, Meir was transferred to Kyiv. Just before leaving the cell, bidding farewell to his comrades, he heard Eydlin whisper: "Nu, a landele, aza yor oyf zey!" ("Well, my country, perish away!")

The investigation into the Gelfond case concluded in the capital of the USSR. In Kyiv, Meir spent a long time in solitary confinement. To keep from going insane, he began reciting books aloud to himself. The investigator, Captain of the MGB (Ministry of State Security) Goryun, even thought that Meir might be feigning mental illness, but just in case, he was transferred out of solitary confinement. There were several cells in the Kyiv MGB prison where Meir stayed. In one of them stayed an old religious Jew who had moved from Moscow to Chernivtsi. Gelfond remembered for the rest of his life how difficult it was for this righteous man to be in Soviet prisons. Once, on a Saturday, cellmates were taken for a typhoid vaccination. An old man begged a female doctor not to vaccinate him on Shabbat, but he was grabbed by the arms and forcibly vaccinated. Meir protested: "How can you do this? You're a doctor!" For this, the guard threw the young man into the "closet" of the investigative body. It was a closed, narrow wooden box where it was impossible to even turn around. He found himself in it more than once.

In November 1949, the investigation into the Gelfond case was completed. At that time, he was transferred to Lukyanivska prison. The head of the new cell was the imposing Mikhail Danishevsky, the chief editor of the central party newspaper of the USSR "Radyanska Ukrayina," who was already serving his third term. Another equally interesting cellmate for Meir was the convinced Zionist Davidovich. Thanks to this old inmate, Gelfond first heard about Herzl, Weizmann, Sokolov, and other leaders of the Jewish people.

Found guilty under articles 54-10 part 2 ("Propaganda or agitation") and 54-11 ("Organizational activity") of the Criminal Code of the USSR, Meir Gelfond received 10 years of labor camps. Together with his comrades, Vladimir Kertzman and Mikhail Spivak, on December 3, 1949, he set off on the stage of imprisonment.

Meir Gelfond ended up in Vorkuta, in the notorious Rechlag, where political prisoners were held. The most dreaded work in Rechlag was considered to be the mine. However, luck was on the side of the former medical student. With the assistance of a Russian nobleman and an excellent doctor, Sergey Petrov, the young Jew ended up in the camp's medical unit. Meir first became a paramedic and then a "brother of mercy." In field conditions, he was mastering his future specialty. Using his privileged position, he always tried to help Jews who found themselves in these dreadful places. Most often, he showed people how to simulate visual impairment correctly, while his senior comrade, Sergey Petrov, in turn, advised the head of the medical unit not to assign the "almost blind" individuals to the most challenging - the "mine" - category.

In addition to studying medicine, Gelfond delved into history, philosophy, and languages in the camp. One of the last Hebrew writers remaining in the Soviet Union, Zvi Preigerzon, who was imprisoned together with Gelfond, recalled that he was the only Jew in the camp who decided to seriously study Hebrew. His diligence and perseverance were incredible. In a few months of study, Meir Gelfond became proficient in speaking Hebrew.

The only consolation in Rechlag was the presence of interesting people. In addition to Preigerzon, Meir Gelfond was imprisoned with a young Zionist from Odessa, Joseph Khorol, a religious Jew and a member of the "Brihah" movement, Mordechai Shenkar, a scientist and a staunch patriot of Israel, Shaya Bilik, a prominent Polish Zionist, Joseph Meller, and many others.

After his release in September 1954, Meir traveled to Zhmerinka to visit his parents. On his way home, passing through Moscow, Joseph Meller asked him to visit Vera Fedorovna Levchak, a therapist who had helped many inmates during her time at the Uchtpechlag. When Meir went to Vera Fedorovna, whose husband was also repressed, he not only conveyed greetings from Meller but also met his future wife, Marina Dolgoplosk, the host's daughter.

Former political prisoners were not allowed to reside in major cities in Ukraine. Having stayed with his parents in Zhmerinka until December 1954, Gelfond was forced to leave for Karaganda, where he enrolled in medical school. Driven by his passion for the medical profession, the former political prisoner excelled in his studies and worked as a paramedic. However, the years spent in the camp only strengthened Meir's convictions. Soon, in Karaganda, he found fellow comrades: former Zionist inmates led by electrical engineer Joseph Kuritsky. Thanks to Gelfond, the Zionists organized the delivery of materials from the Israeli embassy to Karaganda. Meir managed to establish a connection with the Israeli embassy in Moscow through Zionists Menachem Levi and Yakov Eidelman, whom he also met in the camp.

In January 1957, clouds began to gather over the Karaganda Zionists. Meir noticed surveillance on him, and soon his friends from Kuritsky's circle were summoned for interrogations. Shortly after, Meir, returning from a night shift on a work train, was detained for identity verification. The pretext was a theft, but the behavior of the police was peculiar. Familiar with the Soviet punitive system, Gelfond immediately sensed trouble. He had to leave Karaganda for Kalinin, where he continued his studies at the local medical institute.

One more contact Meir Gelfond had with Israel was through his old acquaintance Joseph Meller, who had immigrated to Eretz Israel via Poland. Joining the "Lishkat Aksher" ("Bureau for Liaison"), a special service responsible for contacts with Jews in the USSR, Meller recommended Gelfond as a reliable person. Soon, instructions arrived from Israel for Meir and his beloved, Marina Dolgoplosk, to prepare to leave for Poland. For this operation, fictitious "bride" and "groom" were selected, repatriating to the Polish People's Republic. However, at the very last moment, the operation was canceled. By the end of 1957, the deadline for Gelfond to leave the USSR had passed, and his "spouse," who was already in Poland, had to go to Israel alone.

In late 1958, Meir officially married Marina and moved to Moscow. In 1959, he transferred his studies from the Kalinin Medical Institute to the capital. After obtaining his diploma, he took a position as a general practitioner at the First and Second Medical Institutes. A few years later, the couple welcomed their daughter, Simona.

In the 1960s, Gelfond's Moscow apartment became a place of overnight stays and a headquarters for Jewish activists visiting Moscow from Riga, Kiev, Odessa, Vilnius, and other cities. He maintained contact with the Israeli embassy, receiving money through special couriers who came to the Soviet Union for underground activities. In 1963, under Gelfond's leadership, disparate groups of Zionists successfully carried out their first joint action. His comrade from Rechlag, Joseph Khorol, managed to print and reproduce brochures with poems by Bialik, articles by Jabotinsky, and a summary of the book "Exodus" by American writer Leon Uris in Riga. From Riga, Khorol brought the "samizdat" to Moscow. From there, Gelfond and his colleagues organized the distribution of brochures to cities across the Soviet Union. The "samizdat" was further duplicated on typewriters purchased with funds from the "Gelfond Foundation," operated by typists whose work was paid from the same fund. The network included translators and distributors, all engaged in underground work, constantly risking imprisonment alongside their leader.

By September 1968, individual families in the Soviet Union started receiving permissions to emigrate to Israel. To prepare for the ongoing aliyah (Jewish immigration to Israel), Meir Gelfond decided to change tactics. He transformed separate groups into a unified informal organization with clear distribution of functions and shared leadership. The second ambitious goal was to establish a network of ulpans, including children's ulpans, and to train Hebrew teachers while providing underground courses with educational materials. In the Moscow Zionist community, a new form of mass events emerged – seeing off repatriates to Israel, where people from various cities would gather.

All this risky public activity took place against the backdrop of Gelfond defending his doctoral dissertation on the use of medications in treating heart failure.

In early April 1969, Meir Gelfond, along with Vitaliy Svechinsky, David Khavkin, and Karl Malkin, joined the "founding group" of an informal all-Union Zionist organization, taking responsibility for "samizdat" (underground publications) and fundraising for the central public fund. In mid-August 1969, representatives of various Zionist groups gathered for another meeting. The first day of discussions took place at Meir Gelfond's house, followed by a session at the apartment of Zionist from Georgia, Gershon Tsutsuashvili. Debates about Zionist work in the USSR were heated, but ultimately, the proposal of Moscow residents Gelfond and Svechinsky was accepted. It was decided to coordinate the actions of individual Zionist groups through the "All-Union Coordinating Committee" established during the meeting. Aliyah was proposed to be divided into two groups – "Aliyah Aleph" and "Aliyah Bet." The first group of activists ("Aliyah Aleph") was to seek the right of repatriation for Jews through official channels, while the second group was to engage in "samizdat" and the distribution of propaganda materials.

Meir Gelfond also became one of the creators of the printed organ of the all-Union informal Zionist organization called "Iton" ("Newspaper"). In its very first issue, he published an article about the assimilation of Soviet Jews.

Along with ten other activists, Gelfond became a signatory of a collective appeal to world Jewry. The appeal stated that the State of Israel is the historical and spiritual homeland of the Jewish people, and the aspiration of Soviet Jews is to exercise their lawful right to make aliyah (immigrate to Israel). Subsequently, there was a second collective appeal addressed to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, U Thant, and the Chairman of the 24th session of the UN General Assembly, Brooks, signed by 25 activists. Soviet Jews emphasized that within the country, they cannot find a solution to the emigration problem, and therefore, they are turning to the international organization based on Article 13-2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights ("Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country").

In December 1970, after the announcement of sentences to participants in the Leningrad Case, who attempted to fly to Israel on a hijacked plane, Meir Gelfond sent an open letter to "Amnesty International" and former inmates of concentration camps. The former Rechlag prisoner wrote to the authoritative organization that the harsh sentences to the "hijackers" were merely a consequence of Soviet policies directed against tens of thousands of Jews aspiring to go to Israel.

Among the actions prepared with active participation from Meir Gelfond was the legendary march of the "refuseniks" to the reception office of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, demanding free emigration to Israel. Convincing activists not to hold a protest rally but to go straight to the Communist headquarters, Gelfond composed a petition signed by 24 people. In it, the "refuseniks" demanded that the authorities stop persecuting the prisoners of Zion, ensure the right to free emigration to Israel without workplace character references and parental consent, and guarantee the delivery of visas from Israel.

The audacious action took place on February 24, 1971. Only late in the evening did the group of strikers leave the reception office of the Supreme Soviet, having received assurances of safety and a promise of a prompt response to their collective appeal. A week later, Jews, having received no reaction from the authorities, engaged in a public protest.

The authorities no longer wanted to keep the "troublemakers" in the country. Meir Gelfond received an exit visa on March 3, 1971, with an order to leave the country as soon as possible. On March 9, 1971, together with his wife Marina and their nine-year-old daughter Sima, he flew from Moscow to Vienna and from there to Israel. At Ben-Gurion Airport, Soviet Jewish leader Gelfond, along with other Jewish activists, was personally greeted by the Prime Minister of Israel, Golda Meir.

Meir Gelfond maintained his connections with Soviet Jewry still behind the Iron Curtain. In May 1972, written testimonies were sent from Israel to the General Prosecutor of the USSR, Rudenko. Meir Gelfond, along with former "refuseniks" Mikhail Zand and Vadim Meniker, reported that Joseph Mendelevich, a figure in the "airplane case" accused of writing articles "On Assimilation" and "Jews Stop Being Silent," had no connection to the texts. The Israelis stated that the articles were written by Zand and another unnamed person, with active participation from Meir Gelfond and Vadim Meniker. The signatories also mentioned the defendant Leib Khnoche, to whom the Chekists attributed the possession of "anti-Soviet appeals." This was how the article "Your Native Language" was characterized in court documents. In their statement, the repatriates claimed that the article "Your Native Language" did not have an anti-Soviet character. Gelfond and his associates insisted that Mendelevich and Khnoche should not be charged with the relevant points of the accusation or the verdict.

Upon arrival in Israel, Meir, Marina, and Simona settled in the city of Petah Tikva. In his homeland, Meir Gelfond worked as a cardiologist in various hospitals, including the Beilinson Hospital in Petah Tikva, the Meir Hospital in Kfar Saba, and other locations. Simultaneously, he served as a therapist in Kibbutz Ga'ash. During his Israeli life, Meir Gelfond was known as a principled defender of new repatriates. In an article published in 1976, he explained his position: "Israel has not lived up to the expectations of repatriates and needs rehabilitation." Openly criticizing in the press the absorption principles of those who moved to Israel, from simple workers to scientists, he boldly criticized the Israeli authorities. He also had significant grievances against the leaders of Soviet Jewry, who failed to form a party among their compatriots that would strongly advocate for the rights of repatriates. Gelfond believed that the leaders preferred comfortable positions in the ministries to helping their fellow countrymen.

Such was the prisoner of Zion Meir Gelfond. He was often called the conscience of the Soviet aliyah. Until the end of his days, he remained a truth-teller, faithful to his convictions.

The years spent in dungeons and constant stress undermined his health. Meir Gelfond died on July 8, 1985 from lung cancer. In honor of the doctor and Jewish hero, a memorial plaque was installed at Meir Hospital. His daughter, Simona Abramov, followed in her father's footsteps. She works for the Israeli national medical service, "Magen David Adom."

Bibliography and sources:

Gelfond, M. Memoirs of Aliyah Activist Meir Gelfond and Reviews About Him / Compiled by Y. Melnik. – Jerusalem: Lira, 2008.

Finkelstein, Eitan. Russian Town in the Israeli Kingdom // Znamya. 1997. No. 4, pp. 180-206.

M. Zand, V. Meniker, M. Gelfond. Sworn Written Testimonies. "Sion," No. 2-3, 1972, pp. 109-112.

Butman, G.I. Time to Keep Silent and Time to Speak. Series: "Library of Aliyah," 1984.

New Data on the Leningrad Airplane Trial // Samizdat Materials. 1972. No. 47. — Munich: Radio Liberty, 1972, pp. 39-40.

דבר // הרופא שאינו מ"אומרי-הן, 4.05.1976

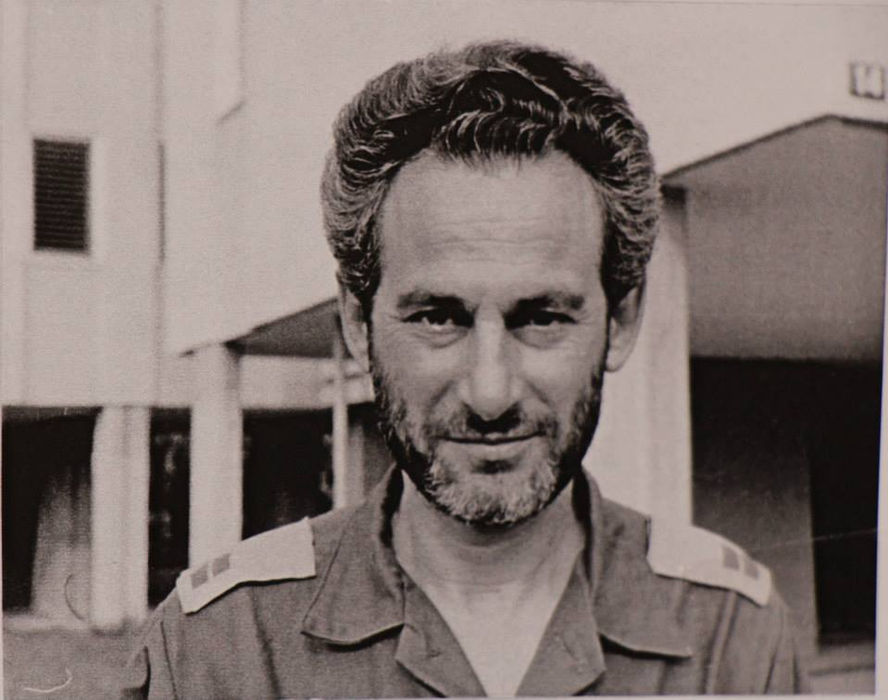

Meir Gelfond

1929 – 1985