Moisey Feldman, rabbi of the synagogue in the city of Bila Tserkva, was arrested by the local city department of the UMGB of the Kiev region on December 19, 1950. He was the main person involved in the “Palestinians” spy case initiated by the Ministry of State Security of the Ukrainian SSR against religious Jews who returned home from evacuation.

Rabbi Feldman was a native of Bila Tserkva: he was born on August 20, 1896. Moisey’s mother died immediately after giving birth, and he and his brother Berku were raised by their father, a butcher who procured kosher poultry for local Jews.

A very religious man, butcher Feldman sent his son first to a cheder, and then to a higher religious educational institution – yeshiva. In 1917, the young graduate returned home and got a job as a salesman. The next year the young man joined his father's occupation. In the company of the Bila Tserkva butchers, Moses acted as a cashier.

In 1919, he, a religious Jew, was drafted by the local Bolshevik authorities to the local guard battalion, which was supposed to be engaged in the protection of public order. Moisey did not serve for long, until the summer of 1919, fell seriously ill and was discharged.

After demobilization, until August 1920, Feldman was on the run: first in Mykolaiv, and then in Odessa. In his hometown, a former soldier of the “red” guard battalion, moreover, it was dangerous for a Jew to be. At this time, Bila Tserkva was occupied by Denikinites, Poles, or even just gangs who did not forget to arrange a Jewish pogrom on the occasion.

When it became more or less calm in the Kiev region, Moisey returned home and soon played a wedding with Reizya, whom he had long liked. In 1922, in order to provide for his wife and newly born daughter, Moisey accepted his father's offer and became his student. With the end of the NEP era, all Bila Tserkva butchers were forced to get a job in the state slaughterhouse at Soyuzutil. Moisey worked there until the beginning of the Great Patriotic War.

Benzion Feldman never stopped teaching his son that communism is evil and fundamentally hostile to the Jewish tradition. The Feldman family did not want to abandon the religion and traditions of their ancestors, so Moisey and several of his friends organized a small group in the city in order to somehow preserve the traditional Jewish way of life and thought. In the midst of mass repressions, in 1937, a Jewish religious society was registered in the Bila Tserkva. According to some reports, Moisey performed the role of a rabbi in the local community.

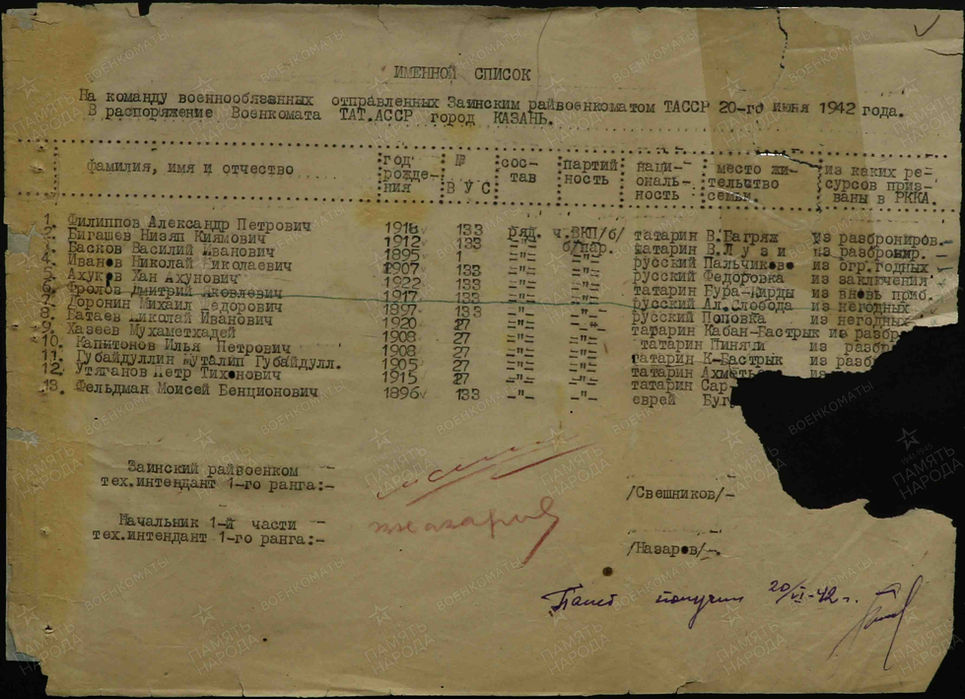

In 1941, together with his wife and children, Feldman was evacuated deep into the Soviet Union. After long ordeals and a dangerous road, sometimes fleeing from the rapidly advancing Nazis only at the very last moment, the Feldmans ended up in the village of Pertsovka in the Zainsk region of the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, where they immediately began to work on a collective farm.

Moisey worked until the summer of 1942, when he received a summons. From June 1942 to the end of January 1943, Moisey Feldman was in the active army.

On August 12, 1942, near Voronezh, Private Feldman seriously wounded his shin. The leg could not be saved. After amputation in the Tambov evacuation hospital, Moisey was sent for further treatment to Kopeysk in the Chelyabinsk region.

Moisey Feldman was declared unfit for military service and after demobilization he again ended up in Pertsovka near Kazan, where he lived with his wife until the liberation of Bila Tserkva.

In March 1944, the Feldmans returned to the Bila Tserkva, destroyed by the Nazis. For four months, the war invalid worked as a salesman in a bread shop, but then he quitted. Several thousand Jews returned to the city from the evacuation, but there are practically no Tanakh and Talmud experts left in Bila Tserkva. The locals asked Moisey to become their rabbi.

Moisey Feldman decided to devote all his free time to the restoration of the Bila Tserkva community, he also tried to speed up the beginning of services that had not been held in the synagogue since 1941. It was not only an urgent need for spiritual food, but also a symbolic act: the Jewish people are alive and will live, and the revived synagogue will be the proof.

The believers began to pray even before the official registration of the community. At the end of 1944, a local Jew Volko Polyak provided his apartment for a minyan, which included 12 people. A few months later, the activists received a note from the Deputy Chairman of the Bilotserkivskiy City Executive Committee Grigoriev, in which it was reported about the inadmissibility of illegal prayer meetings. The city executive committee demanded that believers act exclusively in accordance with the law.

Volko Polyak and Moisey Feldman were delegated by Bila Tserkva Jews to Kyiv, where on April 9, 1945, the Commissioner for Religious Cults under the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR registered Moisey Feldman as a rabbi of the Bila Tserkva synagogue. Volko Polyak received the official position of cantor in the community.

At first, prayer meetings were held at the old address, in the Polyak’s house. However, there were so many people who wanted to visit the synagogue that from January 1, 1947, an agreement was concluded between Moisey Feldman and the Bilotserkivskiy city residential administration for a free lease of the building to be used as a synagogue. This dilapidated wooden building became the center of one of the five Jewish religious communities in the Kiev region that were officially operating in the post-war years.

The Commissioner of the Council for Religious Affairs in the Kiev region noted with obvious displeasure that about 2,000 people visited the Bila Tserkva synagogue on Yom Kippur in 1949 and 1950. Every day there were at least 50 Jewish believers, and even more on Shabbat.

Feldman tried with all his might to preserve the community. To the appeal of several believers in 1949 regarding the organization of a cheder at the synagogue, Moisey responded with a decisive refusal, warning the board that he would be forced to resign as a rabbi if they insist. In accordance with Soviet laws, believers could not perform rituals outside the synagogue, the police did not even allow “shiva” at home - a seven-day mourning for the deceased. Amid harassment for the slightest departure from the very tough demands of the authorities, such an “anti-Soviet” demand as the opening of a religious school – a cheder – could have poor consequences for the leadership of the community and all signatories. When the community's board tried to raise funds for the restoration of destroyed gravestones in the Jewish cemetery, they were immediately accused of “speculation”, and the whole twenty, headed by a rabbi, could well be imprisoned for involving children in religion. Even the closing phrase of the last prayer of Yom Kippur – “L'Shana Haba'ah B'Yerushalayim” (“Next year – in Jerusalem!”) - was regarded by party functionaries as a call to Jews to betray the Soviet homeland.

In the late 1940s, Moisey was summoned to the MGB several times about his wife's relatives who lived in New York. Reizya’s uncle sent a food parcel to the Feldmans from America in 1945. The Feldmans sent a letter and a telegram in response, but for their freethinking they were then forced to report to people in uniform. When another package from relatives arrived from the USA, Moisey simply did not pick it up from the post office.

As a rabbi, Feldman needed religious literature, but he could not ask for anything from American foundations trying to help the Bila Tserkva community. A gifted calendar, as well as the collection of prayers for the dead and Halakha injunctions, bought in the Kyiv synagogue – that was the rabbi’s meager arsenal.

In the fall of 1924, Moisey spent an unforgettable 5 weeks in the dungeons of the OGPU without daylight and fresh air. Then, on the night of September 24, 1924, Feldman was arrested with 40 other young people from Bila Tserkva and neighboring townships, who were members of the Zionist organization “HeHalutz”, which prepared those who wanted to move to Palestine for agricultural work on the land of their ancestors. As it turned out, the Chekists were mistaken: they needed a cousin of the rabbi, also Moisey Feldman, the head of the Bila Tserkva branch of HeHalutz, who managed to escape from the city right before the arrest. Having figured it out, the extraordinary officers freed Moses a week later, but the next day arrested him again – now as hostage, promising to apply the most stringent measures in case the fugitive cousin did not appear to confess.

In the end, the leading core of “HeHalutz” received criminal sentences, and Feldman, despite the fact that he was not a member of the organization, was forced to sign a letter stating that he was breaking with Zionism.

In December 1950, everything began to take on a more dangerous turn. The country was looking for “cosmopolitans” and Zionists, and the role of the latter fits a rabbi like no other. And this is despite the fact that not just a religious figure was imprisoned in the internal prison of the UMGB in Kyiv, but a front-line soldier, a war invalid, who was awarded the medal “For Victory over Germany”.

Moisey Feldman was arrested due to the fact that since 1944, in the language of Soviet protocols, he systematically organized illegal services in private apartments and during prayers slandered the Soviet regime. Moisey also fervently agitated the remaining Jews in the Bila Tserkva to leave the Soviet Union for their historical homeland – Eretz Israel.

On December 24, 1950, the senior investigator of the UMGB of the Kyiv region, senior lieutenant Timko, charged Feldman with a crime under article 54-10, part II of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR – anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation.

Feldman denied any accusations of anti-Soviet activities. But during a night interrogation on January 17, 1950, he said that he was really offended by the Soviet regime, which did nothing for the normal setup of the Jews, which suffered the most during the years of the occupation of the people.

He also admitted that in January 1948 he bought himself a receiver and listened to news from Palestine, as well as the Voice of America.

During interrogation on March 17, 1951, the rabbi again confirmed his testimony about dissatisfaction with the Soviet regime, which, from his point of view, was unworthy of the Jewish population, but dismissed the accusations of nationalism completely.

Moscow demanded an early reprisal. On February 20, 1951, in a letter addressed to the head of the 5th Directorate of the USSR Ministry of State Security, Volkov, the Kyiv security officers reported on the imminent completion of the investigation against Feldman and the arrest of other defendants in the “Palestinians” case.

On March 13, 1951, Feldman was declared fit for sedentary labor. For anti-Soviet and nationalist agitation, fully proven from the point of view of investigator Timko, the rabbi was given 15 years in a labor camp with subsequent disqualification for 5 years. In the investigative department of the Ministry of State Security of the Ukrainian SSR, it was recommended that a disabled front-line soldier be given less - ten years in general camps.

The case did not go to court, but was considered by a special meeting on May 26, 1951. The rabbi was sentenced to ten years in prison, found guilty of committing a crime under article 54-10, part 2 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR.

During a three-year imprisonment in Taishetlag, Feldman met the former secretary of the Palestinian Communist Party, Joseph Berger-Barzilai, who had returned to Judaism, and became his confessor. Feldman enthusiastically told Berger-Barzilai that the attitude of today's Jewish youth towards religion and Jewry had become completely different from that of the older generations. These young people were convinced that Jews should live in their own country.

On August 2, 1954, the Central Commission for the Review of Cases of Persons Convicted of Counter-Revolutionary Crimes, Feldman’s term of imprisonment reduced to five years and, on the basis of the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated March 27, 1953 “On Amnesty”, got released from custody. Moisey returned to his family in Bila Tserkva.

The example of Rabbi Feldman, who, according to the Commissioner of the Council for Religious Affairs, got on the “anti-state path”, was used to justify the attack on the synagogue. If during Feldman's service about 500 people came every day on Passover, then after his arrest – no more than 200. At the same time, there were hardly more than two or three dozen middle-aged people.

State Soviet anti-Semitism, which included the eradication of religion and the fight against dissidents, finally triumphed in this particular city. Once upon a time, Bila Tserkva flourished economically, culturally and architecturally largely thanks to the Jewish community. But the Bolsheviks were haunted by Jewish rituals and alien ideology. The Jews and their heritage were consistently disposed of. In 1917, the city had 18 synagogues, 12 Jewish schools and cheders, and the Jewish population in the mid-1920s was 30-40% of the city's inhabitants. According to the last state census conducted in Ukraine in 2001, there were already less than 150 Jews living here. In 1962, the last synagogue in Bila Tserkva was closed. In 1977, one of the last guardians of the faith, the Bila Tserkva rabbi, Moisey Feldman, passed away. But the memory of him and his companions is still alive.

Moisey Feldman

1896 – 1977