A repatriate from the USSR, Moshe Bar-Zvi from the country of workers and peasants not only left, but fled. He was born on April 10, 1922 in the south-west of Ukraine under a completely different surname – Milman. In the early 1920s, the Milman religious Jewish family lived in the village of Satanov in Podolia (in the Khmelnytsky region). It is not known when the first representatives of this surname ended up in Satanov, but the grandparents of our hero lived in the shtetl for a long time.

At the age of five, he was determined to flee to Palestine, where legendary kings and great battles awaited him. Where Palestine was, Mishka Milman had no idea, but decided that he needed to go to the Soviet-Polish border, which passed not far from the town. Having escaped once from Satanov towards Poland, the boy stumbled upon rows of barbed wire and border guards armed with rifles.

Soon Misha's beloved sisters graduated from the seven-year school and left to study and work in Odessa. From that moment on, Misha decided to follow their example - to study well and move to a city by the Black Sea, where life was not as boring as in Satanov, and besides his sisters, his uncle lived there. And from Odessa to Palestine – a stone's throw.

After graduating from the tenth grade in the spring of 1940, Misha could not leave for Odessa to visit his relatives - he was drafted into the ranks of the Red Army. Already on September 11, 1940, he arrived with a young replenishment in a military unit in the Lithuanian city of Panevezys. A few days later, Misha and his comrades found themselves two kilometers from the new Soviet-German border in the Memel region (now Klaipeda). For several months, the fighters put poles on the border and pulled on kilometers of barbed wire, returning from there to the unit where they learned the basics of drill, learned military songs and the device of Soviet small arms.

The usual army routine did not last long, until the second half of February 1941, when Private Milman was summoned to the headquarters. There, an unfamiliar captain handed the fighter a statement that had to be signed after reading. On the sheet it was written that Private Milman Moisey is asked to be sent to the Chkalov Military Aviation School. The order came to the division headquarters – to send the graduates of the ten-year school to Chkalov (at the present time – Orenburg). The soldier refused to sign.

But the captain demanded that Misha not only sign the paper himself, but also forge signatures on 39 other statements. The next day, during the formation, all the soldiers who “signed” the statements were stunned by the news: two hours later, under the command of Sergeant Yefimov, they were leaving by train for the city of Chkalov.

Of the 40 who came from Sebezh, 16 people entered the flight school. With Milman, another Jew by the name of Zilberman was accepted, and others, including former classmates in the ten-year age, warmly said goodbye to those who entered and drove back to the location of the unit.

On June 22, 1941, Misha did not want to receive dry rations in the canteen and stayed in the hostel. Suddenly, an important government message was broadcast over the loudspeaker. The steel voice of Levitan announced that the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet people against the German fascist invaders had begun.

The cadets that day sat in class until the evening, as if nothing was happening, until everyone was called to the gym to form. The political instructor made a fiery speech to the cadets, saying that due to the increase in training hours, the course of navigators would be released not in a year, as planned, but in 10 months.

Soon a letter came from the sisters from Odessa that their husbands were at the front, and the city was already being bombed by German planes. The mass retreat of the Red Army was not reported on the radio or in the newspapers, but refugees and wounded soldiers who suddenly appeared in Chkalov shared with the cadets the terrible details of the first weeks of the war. There were almost no Soviet planes in the sky, and tank, rifle and artillery units suffered defeat after defeat. Several seriously wounded soldiers who met Misha in the city said that they miraculously escaped from German captivity.

The cadets, and Milman with them, were seething with anger and dreamed of going to the front as soon as possible, but the training of navigators and pilots was not a quick matter.

At the end of October 1942, Milman and his classmates completed the theoretical and practical course of navigators and were preparing, with the rank of junior lieutenants, to go to the front. Excited and enthusiastic cadets received leave to the city and were waiting for the train, which was supposed to take them to the war, but a week later a new order came: everyone remains in place for another course – night flights.

At the end of April 1943, the long-awaited graduation finally took place. In the end, a group of 90 graduates of the school of navigators was sent to Kazan, and then a third of them even further – to Yoshkar-Ola. In early July 1943, Misha and two other navigators were ordered to set up a bombing range on the outskirts of a remote village. At the training ground, it was necessary to build a kind of houses out of wood and keep records of how successfully the cadets-pilots hit training targets.

In August 1943, Junior Lieutenant Milman began to master a new aircraft – the Soviet Pe-2 dive bomber. The study lasted about two weeks and took place in the very center of Yoshkar-Ola.

Before getting to the front, cadet Milman managed to try himself in the role of a paratrooper, having jumped twice with a parachute, and had an accident, having turned over with the plane during landing.

The pilots and navigators, dampened by the front-line soldiers, among them junior lieutenant Moisey Milman, were soon really sent for retraining to the Azerbaijani city of Ganja, which was then called Kirovabad. The 11th reserve aviation regiment was located there, on the basis of which the pilots were trained.

There the navigator got acquainted with the families of Jews who, unlike his neighbors in the town, became so Russianized that all Milman's cautious talks about the land of his ancestors, Palestine, were either ignored or immediately demanded to stop.

In February 1945, a long-standing plan finally began to be implemented - revenge on the fascist monsters. Having mastered the American aircraft “Douglas A-20”, nicknamed “Boston” in Kirovabad, Milman, together with his comrades, was finally sent to the front. They were ordered to arrive in the Polish city of Torun, where the headquarters of the 327th Bomber Aviation Division was located. The division was armed with A-20 Boston aircraft, which were waiting for new crews before a major offensive.

They went to the front through Ukraine, where Misha was able to stay with his sister in Odessa. From her, he learned that none of his relatives and friends were left alive. When asked what plans his brother has for life, if everything is okay, he again shared his idea: “I will go to Palestine”.

The first combat operation, in which Junior Lieutenant Milman took part, took place shortly after arriving at the location of the 408th Bomber Aviation Regiment. Experienced pilots and navigators joined the battle along with the newcomers.

Taking off in the target’s direction, Milman soon saw the Baltic Sea, although the city itself was almost impossible to see due to the clouds of black smoke. “Look! – Shouted the pilot to the newcomer, frightened by strange flashes overboard the car. – They decided to shoot at us from anti-aircraft guns”.

Then everything was like a dream. Bombs began to fall from the lead aircraft, and Misha automatically opened the hatch and pressed the bomb release button. They returned to the airfield without loss.

In the second half of April, the regiment's headquarters moved from Torun to the vicinity of the town of Merkisch-Friedland. From there, in the mornings, they flew to bomb the German rear, supporting the Soviet offensive against Berlin, sometimes for weather reconnaissance. Goal No. 1 of navigator Milman's life plan was fulfilled – he avenged the blood of his dead parents and fellow soldiers.

The day of May 9, 1945 began at the 408th Bomber Aviation Regiment as usual. After breakfast, all the crews were called to the parade, which was to take place at the airfield. The political instructor announced in a solemn voice before the ranks that the German government had signed an act of unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany, but the war was not over for the pilots – their help was needed to put the Japanese aggressors in the Far East in their place. The regiment was waiting for a festive dinner, during which all the technical and flight personnel sang to the accordion and danced dashingly.

Having celebrated the victory over Nazism, the servicemen practically stopped flying. Rumors spread throughout the regiment that the Soviet government should return serviceable aircraft to the United States, and that everyone would be transferred to domestic Tu-2s, having previously sent them for retraining somewhere in the Moscow region.

The regiment's headquarters was redeployed to a Polish town near Poznan, and Milman and his fellow soldiers were sent to study in Russia. Having written a report, Misha received a two-week vacation, which he decided to spend with his sister and niece in Odessa. After successfully completing the Tu-2 course, Milman flew back to Poland.

Once, in March 1946, Major Solnyshkin summoned the navigator to his headquarters. The junior officers escaped with a slight fright, donating a month's salary for the restoration of the Motherland, while Major Solnyshkin had to say goodbye to his salary for three months.

The desire to return to the state, where the government continued to brazenly rob the poor and powerless people, Milman had less and less, and the dream of Palestine became even brighter. The young man changed his mind to enter the institute, but repatriation to the homeland of his ancestors became his main goal.

Soon the senior lieutenant was able to speak with Polish Jews traveling from the Soviet Union through Poznan to the West. They said that their path lay in western Germany, from where they could go to Palestine, ruled by the British.

After several unsuccessful attempts to leave the army, Senior Lieutenant Milman decided to take the risk. Taking a two-week vacation in the unit and indicating as a place of residence a city near Moscow, where the Tu-2 crews were trained, Misha boarded a freight train bound for Germany.

From the German capital, Misha went straight to Erfurt, to an acquaintance Jewish seller who promised to help with crossing the border. He advised Milman to return to Berlin and try to move from the Soviet zone to the American one. Then you had to go to Schlachtensee Street, where the UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Reconstruction Administration) camp was located.

Getting out of a taxi near Schlachtensee Street, Milman quickly found the refugee camp. There was a guard at the gate, to whom Misha addressed in Russian: “I am from the Soviet Union, I want to go to Palestine”. The Russian-speaking wife of the guard, who approached the gate, explained to the former navigator of the Soviet Air Force that he was to be interrogated by an American officer. Milman was asked for a long time about his family, military service, and details of crossing the border. Milman's Soviet military ID and other documents went to the trash can, and he was strictly ordered to remain silent about his past and introduce himself everywhere as a Polish Jew. It was also forbidden to go outside the camp.

A few days later, a large covered truck took a group of Jews, including Milman, to western Germany.

In the new refugee camp, Misha settled with five Jews from Poland. In the camp, everyone was Jewish, but mostly communicated with fellow countrymen. Misha was overcome by a painful feeling of loneliness. Most of the refugees who were going to Palestine had relatives on the territory of the British Mandate, they had good professions. And a significant part of the Jews from the refugee camps did not intend to go to Palestine at all, dreaming of getting to the land of opportunity – America.

One day Misha was told that some guy was looking for him in the camp. After lunch in the dining room, a young man really approached him and immediately introduced himself: “My name is Yitzhak. We are looking for you. They say that you were the navigator of a bomber in the Soviet army, and we just need those. I belong to the Beitar movement, which aims to create a Jewish state in Eretz Israel”.

He warned Milman that it was extremely difficult to get to Palestine from his camp, but groups of repatriates were sent from Kassel every two months to the Middle East.

On the same day, the former senior lieutenant put his poor belongings in a suitcase and left for Kassel. From Kassel, 30 Beitarians left for Paris and settled there at 16 Lamarck Street. They sat locked up for a week, learning the Beitar hymn and other songs in Hebrew by heart. They performed them during the formation in the morning, raising the white and blue flag and marching in the courtyard of the building.

On January 18, 1947, at 13:35, the brigantine Lanegev sailed from the French port of Set towards Palestine.

On February 8, 1947, the weather began to deteriorate, but at night in the distance passengers could see the lights – they were greeted by Tel Aviv. An emissary from Eretz Israel accompanying the flight began giving instructions on what and how to do after landing. But suddenly the ship was illuminated by a sheaf of light – the source was a British warship. Under escort, the sailboat was taken to the port of Haifa, and all illegal migrants were deported to Cyprus.

In internment camp No. 60 Misha – now, at the suggestion of the Beitarians, Moshe Bar-Zvi – had a little rest from his long journey and took up Hebrew in earnest. Not wanting to be bound by the rigid framework of the movement, he and several of his neighbors in the tent left the Beitar.

After a year's stay in Cyprus, on February 18, 1948, the former passengers of the Lanegev were invited to another ship under the loud name “Kadima” (Hebrew “forward”). From Famagusta they sailed to Haifa, and then, under the armed protection of the British, ended up in the Atlit camp.

Finally, another goal was achieved - he made it to Palestine!

Eretz Israel turned out to be far from Poland, to which Misha was going to walk in his distant childhood, in the far Middle East, surrounded by unfriendly Arab countries.

Tel Aviv turned out to be completely different from what the former navigator had imagined. Instead of sands and camels, there were asphalt streets and completely European houses around, and the locals did not look like those Jews who lived in Polish and Ukrainian townships.

Hearing back in Cyprus that, in case of failure in finding work and housing, you can try to enroll in the army, Misha went to the recruiting station. Moreover, this is exactly what they were trained for in “Beitar”. Milman was confident that he, a war veteran and a former Soviet officer, would be useful to the Jewish state. Lishkat ha-giyus four days later sent a negative answer and a certificate of exemption from conscription for 6 months.

The repatriate who found himself without any support was rescued by an acquaintance from Beitar, whom Misha met by chance on Allenby Street. Milman settled in his room and, after working for a month at a construction site, moved on to another job - at the warehouse of the Tnuva plant in Tel Aviv.

Milman continued his attempts to break into the military aviation, but the military registration and enlistment office still gave the standard answer: new repatriates from service at this time have been released. Everything changed in May 1948, after the declaration of Israel's Declaration of Independence. In Tel Aviv, the streets were empty in an instant, colleagues and neighbors donned military uniforms and went to serve in different parts of the country.

The postponement for the olims was canceled, and on June 12, 1948, Moshe Bar-Zvi, an Ole Hadash from the USSR, became a fighter of an artillery battery. At Misha's insistent proposal to send him to the aviation, the officer just shrugged his shoulders and said that the Motherland needed good artillerymen. After several weeks of training, the newly minted artillerymen received an order to move to the designated place and open fire. As it turned out later, Misha's crew shot at a distance from the airport of the city of Lod. Then there were battles near the village of Beit Nabala, where Milman's battery hit 2 of 10 Jordanian armored cars that launched a counterattack.

During the armistice, on July 18, 1948, when the battery was stationed near the former German colony of Wilhelm, Milman again decided to try his luck at the Israel Defense Forces Air Force headquarters. After a severe exam, Misha was issued a request signed by the aviation headquarters for his transfer from artillery to aviation.

Together with two immigrants from Poland, who graduated from the same flight school in Chkalov in 1944, Misha began to study a new type of flight for himself – over the sea. Soon, former navigators and pilots from South Africa, Canada and England joined the course.

While serving at the Air Force headquarters, Milman, together with the Canadian pilot Kaplansky, made reconnaissance flights on the Rapid aircraft to the Shechem region, Tul-Karem, and was also responsible for the transfer of supplies to a base in the Negev desert.

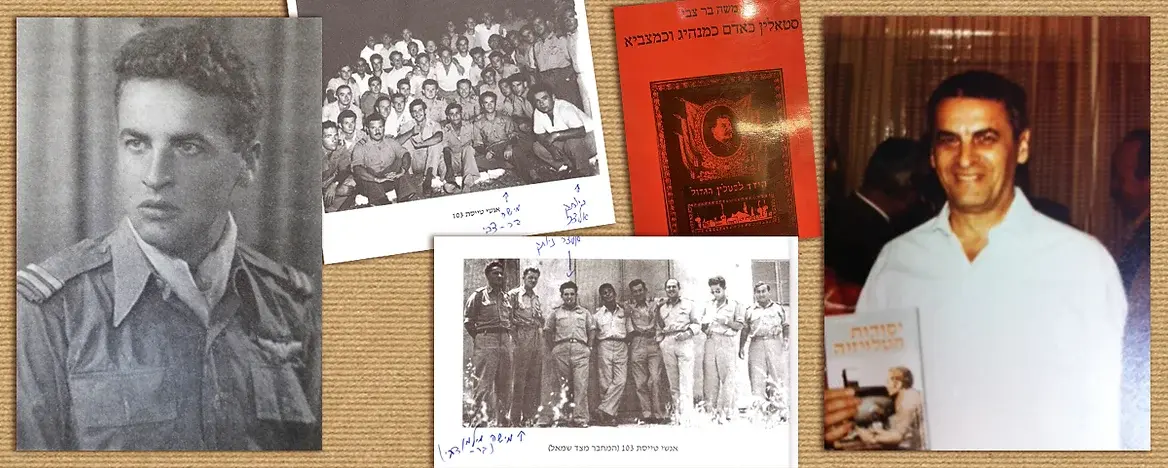

In October 1948, Misha was sent to the Ramat David base, where the 103rd Israeli Air Force Squadron was located, which was engaged in bombarding enemy positions and transporting goods. In addition, he participated in the bombing of Gaza and Rafah, in December of the same year he flew to bomb the Egyptians in El-Arish and Fallujah. In March 1949, his plane took an active part in the last operation of the Israel Defense Forces in that war – the capture of the Gulf of Eilat.

After the war, Milman continued to fly the Dakotas and British Mosquito bombers to the south of the country with the 103rd Squadron. Subsequently, he was involved in the drop of paratroopers and aerial reconnaissance over the Mediterranean coast.

In the early 1950s, a former Soviet soldier trained navigators at the IDF flight school. Many times he flew to topography the Negev and Galilee, as well as to artificially induce precipitation in the Beersheba region.

In 1955, Moshe Bar-Zvi, a major, was discharged due to illness. The front-line soldier faced another war - with a cancerous tumor. A native of Satanov withstood this terrible and long-term battle, he was supported by his wife Mina. Until 1988, he worked as a television technician, and in his spare time developed training courses related to television and computers. His books on television technology gained recognition in Israel and were used for a long time as textbooks.

In retirement, the veteran published a memoir and a book about the Soviet dictator – Joseph Stalin. On March 15, 2001, Moshe Bar-Zvi passed away. Taking revenge on the Nazis, he, as planned, fought and died in the country of the Jews.

Moshe Bar-Zvi

1922 – 2001